With Stacy Szymaszek's 11-year tenure as Director of the Poetry Project coming to an end and the search for a new Director well underway, I recently returned to the listings of the St. Mark's Poetry Project Collection in the Rare Book & Special Collections Division at the Library of Congress. Former Director Anselm Berrigan oversaw the acquisition of the Project's Archives by the Library of Congress in 2007 and the over 1,000-item collection--including decades of recordings, flyers, newsletters, and ephemera--is described as "probably the most significant [archive of] post-war poetry readings in existence." Because the collection is still unprocessed, I started corresponding with librarians at the LOC a few years ago about particular materials, lists of recordings of specific poets, and other information. The last I heard, batches of digitized recordings of poetry readings were beginning to be processed, though I haven't been able to access them yet. When this collection becomes available it will be a windfall for scholars of the New York School and the history of poetry in New York City.

But for whatever reason there is one item, and one item only, from the sprawling Poetry Project Collection that is currently available online--an item described as "Notebook of Bernadette Mayer, Project Director of St. Mark's Poetry Project, 1980." Mayer was the Director of the Project from 1980-84, preceded by Ron Padgett from 1978-80 and followed by Eileen Myles from 1984-86, and this notebook, available as a full-color 182-page PDF is a fascinating, vibrant document of Mayer's work as an arts administrator. It is, essentially, a record of Bernadette at work, a swarm of notes and reminders and information that keep one's daily responsibilities manageable, or at least traceable. In What's Your Idea of a Good Time?: Letters & Interviews 1977-1985, Mayer's letters to Bill Berkson, contemporaneous to this notebook, often mention her work at the Project. "Meanwhile," she writes in January 1981, "I've become (as I think anyone would) obsessed with Poetry Project. But I don't like other people's attitudes to my so-called authority--if only it were sexier--the directrix!" Full of love and gossip about the Project, her friends, and their thinking, the correspondence in What's Your Idea of a Good Time? also tracks the development of Mayer's book Utopia. It probably doesn't come as a surprise that working at an independent arts institution with the history and personalities of the Poetry Project would make one wish for a genuine utopia, whatever that might be. (Mayer imagines it as a lot of things, including a jail for landlords and utopia chairs). Being able to read this notebook, created amid the social and political ruckus of the Project, adds another layer to how deeply and naturally interrelated Mayer's work as Director was with her poems in the early 80s.

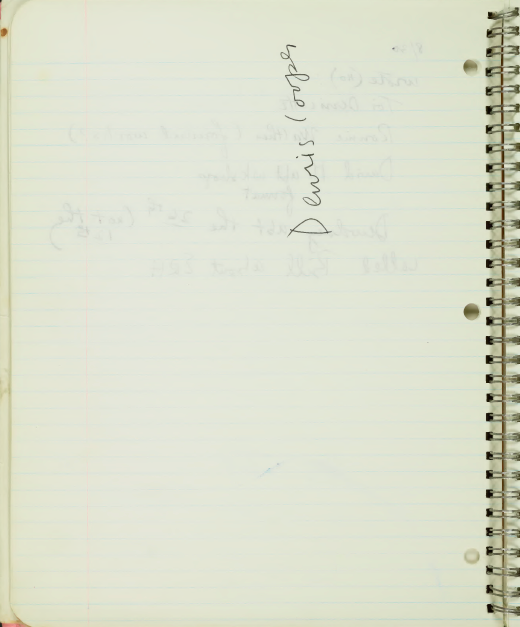

Filled with scribbled notes, poets' phone numbers, lists of names for possible readings, reminders, budget concerns, doodles by her then-young children, sketches of correspondence, questions, ideas for events and poems, and even a colored map of the Church describing volunteers' responsibilities for the 1980 New Year's Eve Benefit Reading, the notebook acts as an animated snapshot of the planning and record keeping that went into the events and readings that facilitate and support a community of major artists. It's an incredible visual document. From day-to-day Mayer is checking in with Alice Notley about a poster, calling John Wieners, writing to Cecil Taylor, or checking to see if a grant application for the Project Project Newsletter is due yet. A few of my favorite entires are a page that just says "Dennis Cooper" written vertically, doodles by Mayer's children Max and Marie Warsh, Bernadette's own doodles (clearly made during meetings), and the cover itself, with its loose arrangement of notes, quotes, and annotations, like altering "College Ruling" to "College Reagan Ruling" and the sketchily-housed "LOVE."

More than anything else, the notebook is a document of labor, evidence of the difficult and overwhelming work that it requires to manage an institution like the Poetry Project, including managing the personalities, egos, and arguments amongst artists and other Project employees. Perhaps the most significant document in the notebook is a three-page letter from Mayer to Bob Holman, then Coordinator, host, and workshop leader at the Project, which seems to have stemmed from Holman objecting to Mayer allowing people to smoke and drink during readings in the Church:

Dear Bob,

I'm your friend. I was your friend before I was "director" of the Poetry Project, before I knew anything about it except to teach my workshop. We work at the Poetry Project, not personally ambitiously (I hope) to further this nearly political cause, we believe in poetry. I didn't take this job for the money (the way Ron presented it to me). I took it because it's more important to me to help run the Poetry Project than to teach, etc. Also it was a chance for me + Lewis [Warsh] to live on the Lower East Side among all our friends.

Mayer continues, echoing a feeling she described to Berkson in a July 1981 letter--"I'm appalled by habits and having to be only one person":

I don't like to ever be treated like a person in a state or position of authority.... I guess maybe that is an exacerbating request--to ask to be treated as a friend, but I don't think the formality of our administrative tasks should so overwhelm us that the pleasure's not in it.... I don't like rules--in my life + in my writing I have always tried to at least see what it was like to flout them, thus perhaps my leniency at the smoking + drinking that takes place, willy-nilly in Parish Hall....I would guess I am not suited to my job because, within it, as you can see, I still want people to love me, as if it were the same as writing poetry. Maybe Ted is right + I shouldn't be the person doing this. It's true I'm not lacking for things to do. + if it begins to seem inappropriate + impossible, it won't be hard for me to cede to another.

But as it stands, I feel devoted to my task, if I can do it. Which means if we all can do it, obviously, since it's no longer autocracy.

I'm sensitive too, silly to say, + as a friend I'm begging you to know that, thus this silly letter, with all its pleading to you to be a friend + sillily help me.

It all settles, but squabbles and frustrations are ongoing. Not long after, Mayer and Holman are composing a dialogue by handing the notebook back-and-forth during a Gerard Malanga performance that both of them are particularly upset about. "This is a huge mistake," writes Holman. "I can barely stand to stay in the room," Mayer responds. The tension was interpersonal, as well. In her notes on an early Advisory Board meeting that included replacing current staff Mayer writes, "Ron doesn't want to comment on Eileen Myles." (In their novel Inferno, Myles responds in kind: "[Ron] was an American kind of phony. There are many kinds of fakery, and some are successful. I think I have Ron's figured out.") Next to the bitter, inevitable clashes and falling-outs--an ongoing narrative of all aesthetic and social communities--Mayer's own frustrations surface in other ways: "Oh poem I am so sorry / [...} / What time is it? / What was poem? / I want to weep when the men outside / Accost me + say, 'five dollars for the two of us?' / Perhaps I'm weak, we are in our 'work clothes' / [...] / All of me is forthcoming." Her authority, whether she relishes it or not, her title (Director or Directrix), and her accomplishments are nullified and tinged with self-doubt after being verbally assaulted. The invisible labor, stress, and abuse of running the Project as a woman, a mother, a poet, a friend are embedded in these lines, and evident throughout the notebook, and Mayer uses that pain to exceed the boundaries between her roles and positions: "All of me is forthcoming." Being forced to be objectified and forced to deal with some male poet's bullshit were daily practices. Mayer is there, and refuses. "I'm not you," she writes on the cover.

Read Szymascek's essay "A Good Job for a Poet" about her work and approach to directing the Project that went up yesterday at the Poetry Foundation's Harriet Blog:

I like being a minor public figure. It suits me. I like showing up in magazines, going to parties, being interviewed on the radio, and doing all the figurehead stuff. I also like paperwork and pencils, efficient online grant application systems, making budgets when other people set up the Excel sheet, and attending to the details that go into making poetry readings and writing workshops happen. I wonder what I would have made of the words “infrastructure poet” when I was a teen, if Anne Waldman had been my career counselor? Through our informal mentorship, I’ve come to understand this title as a call to strengthen the sites and discourse and etiquettes that are important for poets to thrive. Anne and I had a conversation about our work in the Brooklyn Rail in 2016. Like her, I have been inspired to make sure the Project represented a larger voice than my own so that its usefulness to the community would outlive my tenure. Sometime people have rightfully said that I have been selfless, the job thankless, that I have been a caretaker; however, it is also important to note that the Project has given me a surplus of self (future?), and I can now envision anything—even writing books that have nothing to do with my life as a nonprofit arts administrator. In June, I will leave the Poetry Project, and I will feel the best kind of lost.

With a Taurus twist, I'm sure Mayer would agree.