I recently started to read The Poetry Project Newsletter as a complete run, starting with the first issue—published December 1, 1972—with the goal of reading them all chronologically over the month of August, at least up through the 1990s (or about 175 issues). As the (mostly) monthly news supplement of The Poetry Project, the Newsletter is full of all kinds of information, like publication info for new books and magazines, calls for work, event announcements, local New York City and national poetry news, reviews, commentary, strong doses of gossip, and a consistent undercurrent of lively resistance to the genre of the “official” newsletter. The various editorial voices are always up to something and the poetry news comes, as it should, a little slant. The Newsletter offers an incredible set of lenses on the history of the Project, and as an enormous stockpile of information that’s gone mostly untouched by literary scholars (the full run from issue #1 to the most recent, #261, is probably somewhere between 2,000 to 2,500 total pages), there’s a lot of great stuff buried in there.

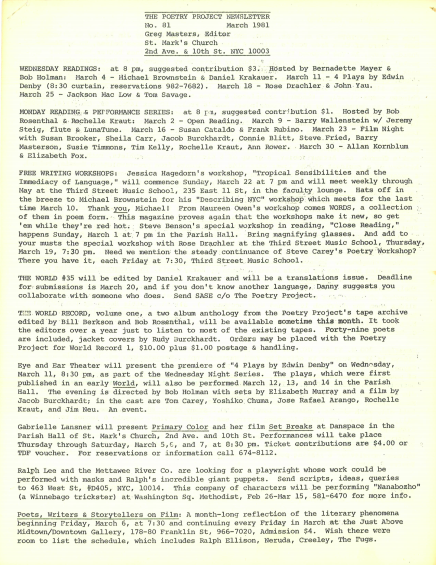

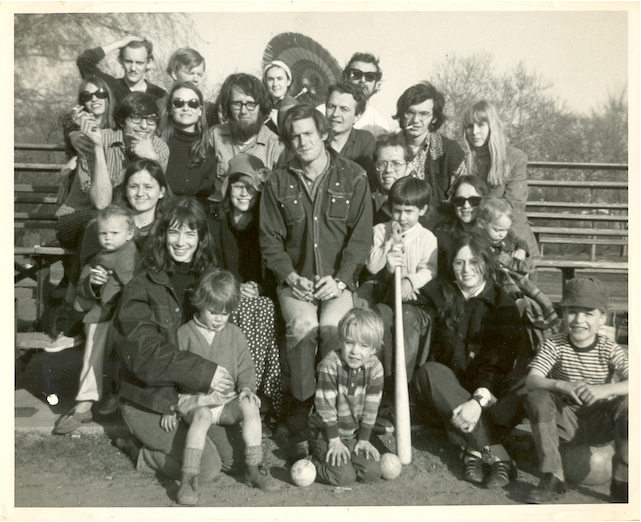

Front page of The Poetry Project Newsletter No. 81, March 1981.

As I was printing and stapling copies of the Newsletter gathered from the Project website (they have about half the full run available to read and download; the other half I’ve been making copies of at Emory University’s Rose Library archive), I happened to read a note written by Greg Masters in Newsletter No. 81, from March 1981. Masters, who was then the editor of the Newsletter, is filling in the Project community on why a TV crew has been filming recent events at the Church. As he writes, “they’ve been filming in 16mm what must now be a few hours of Poetry Project events for what will eventually be cut down to a 15-20 minute segment for the Swiss TV show ‘Schauplatz’ which Mr. Suter [the director] described as a sort of cultural ‘60 Minutes.’” Of course, the Project is no stranger to a documentary attitude toward its programming. Since at least Paul Blackburn’s heroic lugging of a reel-to-reel recorder around the New York City poetry readings that were the immediate precursor of The Poetry Project events, the Project has consciously documented its existence in multiple forms, an activity that the Newsletter is very much a part of. As Masters suggests though, that doesn’t mean that a professional camera crew at the readings isn’t evidence of a new energy around the Project: “[T]he fact that a pro group with camera needing tripod has been showing up occasionally to document what encourages us further to feel is worth documenting, adds to the already exciting sense of ‘something’ happening this year, as continuous as past years, at St. Mark’s Church.” The events that Masters describes them filming—Ted Berrigan and Steve Carey at a United Artists book party, a reading by Elio Schneeman, a mimeograph machine in the Project office—sound like an interesting cross-section of the Project’s activities, from showing the community’s generational range (Berrigan to the young Schneeman), documenting social literary events like a book party (of which, unlike most readings at the Church, there are not audio recordings), and in terms of seeing the Project’s inner workings. “I think we’re all hoping to be able to someday see all the footage they’ve shot here,” writes Masters.

Excerpt from The Poetry Project Newsletter No. 81, March 1981.

Unfortunately, it seems that no one ever saw any of the footage, nor did anyone get to see—and perhaps this isn’t surprising in the early ‘80s—the actual episode of the Swiss TV show “Schauplatz,” which translates roughly, I think (?), as “Location” or “The Place.” But this note by Masters was enough to get me looking for some trace of this footage. Surprisingly, it didn’t take long to find all 10 years of Schauplatz, which ran on Swiss TV from 1980 to 1990, digitized on the contemporary station’s website. A few searches later and I’d found it, the episode of “Schauplatz” titled “New York Poetry Project,” which aired on February 9, 1982, about a year after the initial filming in New York. However, the episode isn’t viewable outside Switzerland due to geoblocking. After some circuitous VPN work, I managed to access and make a copy of the episode—now shown here for the first time. (See below.) Even for a literary community that so thoroughly documented itself, the “Schauplatz” episode is an incredible living document that exists as the only known audiovisual recording of the Project of its kind from this era.

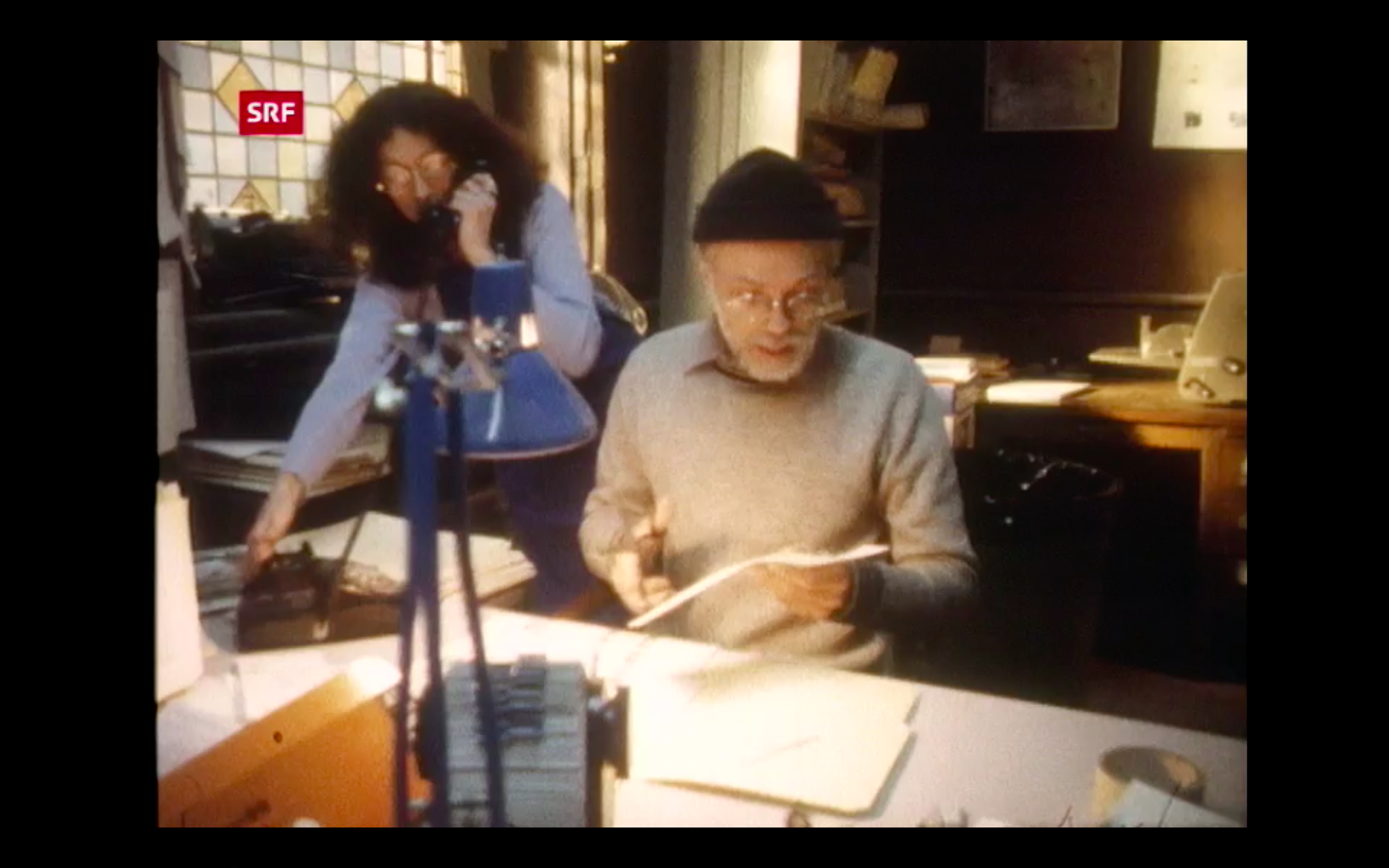

Bernadette Mayer recording Wednesday night reading by Elio Schneeman and Rebecca Wright on January 28, 1981.

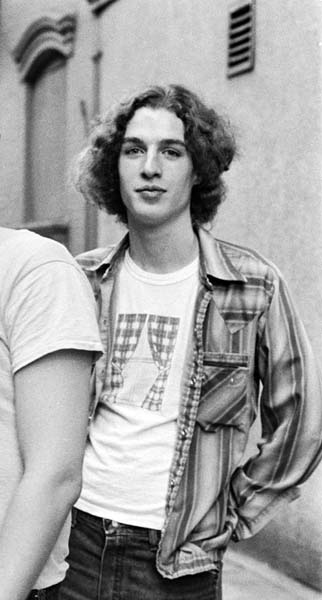

With Peter Wehrli as host, and as Masters’s description suggests, the 16-minute segment documents a stunning range of the Project’s vibrant community in the early 1980s. Here’s a detailed (and half-rushed) accounting of what the episodes takes us through: opening shots of the IBM electric typewriter and Gestetner mimeograph machine in the upstairs Project office; Elinor Nauen voting—likely for Project Board Members—with Ed Friedman in the red plaid shirt; Allen Ginsberg at his two-day special lecture/workshop on the history of metrics, which we see more of later; a shot of a crowd with Rochelle Kraut passing by looking directly at the camera, which then settles on George Schneeman in a brown sweater; the inimitable Barbara Barg playing with Mike Sappol and Joel Chassler as the all-poet band Avant Squares; some incredible shots of the intersection at E. 10th Street and Second Avenue as well as the scaffolding and construction on the Church, which had been severely damaged by a fire in July 1978; Assistant Director Bob Holman, who compiled the "Oral History of the Poetry Project” in 1978, describing the Project’s history; an absolutely amazing shot of Nauen next to Bernadette Mayer, then the Project’s Director, with a baby on her back, at the table with Friedman and Ted Berrigan; Gary Lenhart placing his vote; Holman—with Lewis Warsh in the shot behind him—overseeing a Community Meeting in the Parish Hall (we see Steve Levine, Ron Padgett, Lenhart, Regina Beck, Barg, Cliff Fyman, Susan Cataldo, and others). What else? There’s an incredible warm-light scene of Padgett and Maureen Owen in the Project office as the Gestetner runs off copies, Padgett cuts some paper, and Owen answers the phone while spinning back across the room to manage the mimeo—not easy!; Mayer discusses Project funding as we jump through a montage of shots around the Project offices—flyers and posters, stacks of paper, big sheets of paper where it looks like the names of everyone who has recently read at the Project are listed, and Holman at the typewriter with the reel-to-reel running in the background. The full multimodal behind-the-scenes environment of the Project at work. We also get 19-year old Elio Schneeman and Rebecca Wright giving a Wednesday night reading on January 28, 1981, complete with Mayer managing the recorder with Kim Jones, Gerard Malanga, Pat Padgett, and Katie Schneeman in the audience. Then an incredible crescendo, for me at least, in Ted Berrigan’s interview. I’ve never seen a video recording of him speaking outside of giving a reading. The vividness of his voice and facial expressions is really astounding to me, especially the expressiveness of his eyes. Before the dubbing sets in, we can hear Berrigan say “I taught the first poetry workshop here [in 1966]. One year I set up the chairs for the readings every week, for which I was paid five dollars, which I needed very much.” As Berrigan speaks we see Rene Ricard holding a copy of Jim Brodey’s new Judyism and then Steve Carey signing a copy of his new The California Papers for Daniel Krakauer. It’s amazing to see Brodey signing a copy of Judyism with two pens simultaneously: “For Mike, Eternal Love.” And there’s more! But you’re going to watch it anyway. The segment closes with Wehrli back in the studio showing the audience a set of German translations of Ginsberg’s books as well as a copy of Guillaume Apollinaire is Tot, a compilation of Berrigan’s work translated and edited by R.D. Brinkmann that was published in 1970. This places the “Schauplatz” episode in a lineage of German-language interest in the aesthetics of the New York School that reaches back to German translations of O’Hara from the late 1960s.

So here’s the full segment below. The audio is a little wonky and of course the Swiss German dubbing covers up much of what some of the writers say, but I’m hoping to be able to translate everything back to English to add subtitles and to make a complete transcript available. Just today the video made it around to many of the poets you’ll see here. An initial chorus of responses via email: “What a thrill. Holy Moly.”—Greg Masters; “OH OH OH. WOW WOW WOW.”—Elinor Nauen; “This is so fabulous!”—Maureen Owen; “I was pleasantly stunned.”—Ron Padgett; “How amazing to see ‘us’ so long ago.”—Steve Levine; “Unfuckingbelievable.”—Bob Holman. I agree with everyone. The Poetry Project has been running for 54 years. Here we get a view into the Project when it was just 15 years old and being led by Mayer—one of the most revered avant-garde American poets of our contemporary moment—out of the crisis of the 1978 fire. The early ‘80s were the end of an era at The Poetry Project and within the community of New York School poets on the Lower East Side. This video documents those changes vibrantly and with renewed material specificity.

Many thanks to Greg Masters for his ongoing generosity in pointing out the full cast of characters here and for writing the original Newsletter post that led to all this. Thanks, too, to everyone who responded to and shared the video so far.