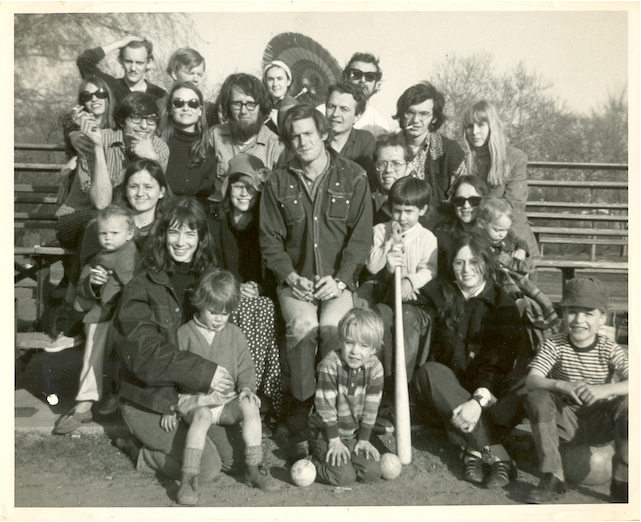

Easter Sunday, Staten Island, 1968. Elio Schneeman with ball cap in lower right corner. Photograph by Larry Fagin.

In February I Think by Elio Schneeman (C Press, 1978). Side stapled, 22 mimeographed pages with covers by George Schneeman.

In New York School Painters & Poets: Neon in Daylight, Jenni Quilter illustrates a distinction between the personal and aesthetic worlds of first- and second-generation New York School poets by pointing out that in the photo to the right, in contrast to most group photographs of Ashbery, O'Hara, Rivers, Freilicher, and the like, adorned with khakis, cocktails, and pressed collars, in the photograph of the second generation poets "the children almost outnumber the adults, they are in the middle of a softball game at Staten Island, and a certain scruffiness is de rigueur." The families, partners, and children of the poets of the younger New York School artists have always lovingly crowded my own reading of their work, not only because so many of their relationships were with other poets but because some of their children, now adults, are also established writers and artists. I'm thinking of Ada Calhoun, the daughter of Brooke Alderson and Peter Schjeldahl, whose terrific St. Marks Is Dead: The Many Lives of America's Hippest Street was published in 2016, or when I recently walked into a gallery in Atlanta to be surprised by a set of photo collages by Max Warsh, the son of Bernadette Mayer and Lewis Warsh. From Amiri Baraka's haunting, anxious, traumatic "Preface to a Twenty Volume Suicide Note," in which "I tiptoed up / To my daughter's room and heard her / Talking to someone" to Alice Notley's Song For the Unborn Second Baby that begins "Pregnant again involucre / (sounds gorgeous)," studying these poems also means studying families.

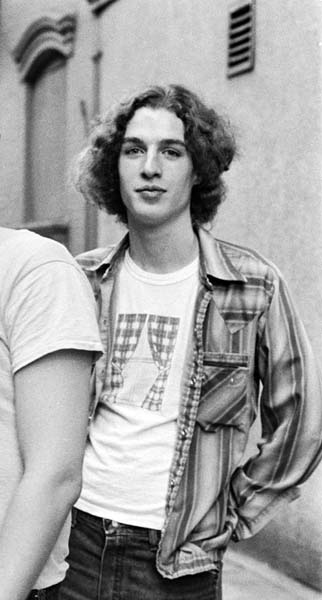

Elio Schneeman wearing t-shirt with George Schneeman print

Elio Schneeman, the son of artist George Schneeman, pictured wearing a baseball cap in the right corner of the above photograph, is one of the New York School children who became a New York School artist in their own right. Born in 1961, Elio was a teenage poet when Ted Berrigan and Alice Notley moved back to New York City in the mid-70s. The Schneeman's St. Marks Street apartment had been a social and artistic common ground since the mid-60s and George's increasing collaborations with Ted and Alice upon their return to New York put Elio in intimate proximity to his father's friends. In the fall of 1978, when he was 16 years old, Elio attended a series of workshops led by Berrigan at the Poetry Project, a friendly and serious occasion for mentorship and aesthetic education that led directly to his first book, which would be published by Berrigan. "Last night Elio Schneeman came over and said he’d like me to do a 'C' Press book by him," Ted writes in his journal on October 4, "I said sure." Reading Ted's journal over the next few weeks is a dreamy illustration of just how casual and collaborative the publishing process could be among the Lower East Side poets. October 16: "Tonight we took presents to the Schneeman’s for Elio’s [17th] Birthday. I gave him NO BIG DEAL, Tom Clark’s Mark Fidrych book. Alice gave him an opal, and the kids made pictures for him." A day or so later: "Tomorrow Bob [Rosenthal] + I run off Elio’s book at the Church, a 'C' Press book now called IN FEBRUARY I THINK. I finished typing the stencils tonight....George did a terrific cover and back cover for Elio's book." October 20: "George, Elio and I collated half of Elio’s book, which is beautiful with George’s front and back covers, tho my typewriter leaves a lot to be desired." October 21: "Today Alice + George + Steve [Carey] + Elio + I finished collating Elio’s book." From start to finish, In February I Think was planned and printed in less than three weeks, just in time for the St. Mark's Church Fire Benefit event at CBGB on Saturday October 26, for which Berrigan was the MC. A fire had badly damaged the Church in late July 1978, more than a dozen years into the experiment of the Poetry Project. Poets like Paul Blackburn and Carol Bergé had helped established the Project in 1966, but the fundraiser at CBGB was a punk-driven reconfiguration of the East Village scene of the '60s. In his notebook after the event, Ted lists his “Heroes,” “Losers,” “First Team,” “Winner,” and “Rookie of the Year” for the CBGB reading. Among readings and performances by Allen Ginsberg, Anne Waldman, The Erasers, John Ashbery, The B Girls, and Richard Hell and the Voidoids featuring Elvis Costello, Elio earns the title "Rookie of the Year," the same distinction Ted half-jokingly gave himself after his reading at the Berkeley Poetry Conference in 1965. It's fitting then that In February I Think would turn out to be the last ever "C" Press publication, the final title in a mimeographed hall-of-fame list of books that began with Ted's own The Sonnets in 1964.

Elio's is the first "C" Press book I've actually owned, thanks to Kevin Killian, who generously gave me his own copy of In February I Think, a copy signed "For Bob Callahan / Love, Elio." Callahan was a Bay Area poet, editor, publisher, and "raconteur extraordinaire," according to his 2008 obituary, who co-founded the Turtle Island Foundation, a press whose catalog includes the elegant first edition of Bernadette Mayer's Midwinter Day. George Schneeman's front cover, a casually tossed off pair of black Converse sneakers, and back over, a stoic, handsome portrait of Elio, convey the mixture of adolescent spirit and the timeless, archetypal imagery that color Schneeman's poems. From the book's opening line, "Future references lead us nowhere," Elio marks an interest in looking at the now but not through his parents' friend's versions of New York School dailiness. While these poems are very much in New York, or "Soot City" as one poem names it, they portray the city as an environment to unfix with imaginative leaps into more unmappable, unconscious spaces. For example, the poem "Unstable Life Form State" begins on First Street and quickly moves to "a cove or inlet of the sea / where mountains once capped the snow towers." These grand, archetypal environments that appear throughout the book--the sea, mountains, a green land--are spaces of possibility and perspective, "adjoining landscape[s]" parallel to daily life and the street. The last lines of this poem are Schneeman at his best, gathering an enigmatic and dreamy sequence of images that reorder scale and sight: "outside, black / figments of the day thru a glass jar / stamp their effects on your periphery." Adding to this movement away from city sidewalks and the need "to shield the world of traffic," In February I Think is full of similes, simultaneously direct and indirect, that gain momentum in their comparisons until the "like," the technical hinge, begins to fall away, and Schneeman's cascade of comparisons transform into a gathering litany of generative associations. It's difficult not to enjoy a simile as joyfully incongruous and correct as "the business of relatives like some amber / hoax" from "The Jewel Staircase." I'm stunned at how completely the truth this line is, at the thinking that allows it to accumulate on the page, and at the wild textures of "some amber hoax." There's something wonderfully liminal in these poems, written within the strange growth of being 16 years old and yet in proximity to so many incredible older artists. The writing reminds me of those addresses that include half numbers, a residence complete unto itself, full and lived in and unique, but also irreducibly between. And while In February I Think is between generations, is in fact generational within the New York School, it also erases our odd, beloved dependence on "generations" to describe the New York School. "This relevance completely dumbfounds us," Schneeman writes, propping up a disregard for categorization, "who go on baffled by the instances / of time." From the end of "Channels": "The time sequence is of a new order / you really aren't where you think etc." I'm imagining that last line floating into view throughout the day, uncannily repeating on street signs, marked on walls, scrolling through a news feed, as a kind of wisdom or resistance or both. Funny and terrifying, it'd keep us alive.

I'm particularly interested in Schneeman's "Sonnet" dedicated to Berrigan, a formal sonic wobbling that begins with an off-balance, humorous near-statement of poetics "Symbolism objects equal footwear" and ends with the Spicerian "on the poem that never ends." Thinking of how instrumental Ted is in these poems, from Elio's workshop with Berrigan at the Church to In February I Think being published as a "C" Press book, it's hard not to read the line "you feed me lunch of cabbage and orchids" as a nod to Schneeman's personal and aesthetic apprenticeship to Berrigan where the common and the dazzling continuously mix and sustain, allowing one to "wrap [and] unite stuff." Whether in a "chintzy daze" or looking out of "hornrimmed glaciers," uniting stuff is exactly what the poem allows us to do. Reading love is reading "Sonnet" next to Elio's "To the Muse," a poem for Ted written after his death that appears in Nice to See You: An Homage to Ted Berrigan. The earlier orchids seem to magically reappear: "I'm always around if you want to visit. / We'll make each room our own, / Where I'll exhale fresh flowers, / Because of you." Fiercely devoted, near, and complexly aligned, I am totally overcome and in love with this poem's articulation of lineage and grief. "I need you to get me into the sky." In 1997, a few months after the death of Allen Ginsberg, Elio would die at the age of 35. His obituary in The New York Times describes him as "Poet. Son of George and Katie Schneeman." His funeral was held at St. Brigid's Church on Avenue B and 7th Street, the same church memorialized in Frank O'Hara and Bill Berkson's collaborative Hymns of St. Bridget ("My heart is corresponding oddly and with odd things," they write), a landscape, it seems, where the poem never ends.

One of the few descriptions of Elio's poetry comes from Vincent Katz, another son of the New York School born just a year before Schneeman. The following is Katz's blurb for Schneeman's A Found Life (Telephone Books, 2000), a posthumous collection:

George Schneeman with Elio Schneeman: "We lie in thick forests...," 1991 ink and collage on illustration board, 11'' by 8.5'' (from George Schneeman: Painter Among Poets).

Elio Schneeman's poetry, while filled with emotion and clear-eyed as to his own motivations, still seems to want to exist in a realm apart from daily life. Dreams, mists, evanescence are the dominant forces. It's difficult poetry to categorize --- poetry of nothingness which is not Zen but rather candid observation of daily patterns: 'the delicious drowsiness / of late afternoon, that slips / invisibly into evening,' as one poem concludes. His word patterns and rhythms are sure; they lull the reader into a dreamlike state, which is sometimes broken by odd turns: 'I want to caress / each layer of skin / like a fine fabric / to encase me in...' An almost Surrealist tone brings to mind Phillipe Soupault's Last Nights of Paris, which also traced visions vanishing on city streets. Elio Schneeman's poetry stands on its own and will.

In addition to In February I Think (1978) and A Found Life (2000), Elio's work also includes Along the Rails, published by United Artists in 1991, about which John Godfrey writes:

Elio Schneeman turns some interesting corners in ALONG THE RAILS. His writing is strong, often quite sophisticated. He is sometimes boyish or raw, but he writes smart, and his perceptions of feeling--real feeling, oblique feeling--are only self-conscious enough to be smartly written. I am impressed by how substantial he sounds, and how solitary.

Photograph of Elio Schneeman by Greg Masters. Courtesy of Greg Masters.

"Words For Greg" by Elio Schneeman, on print by George Schneeman. Courtesy of Greg Masters.