Poems: The Location of Things, Archaics, The Open Skies by Barbara Guest (Doubleday, 1962). 95 pages, hardcover with cover drawing by Robert Dash.

In January 2017, Brandon Shimoda sent me a message on Twitter that he had a copy of this book by Barbara Guest, he said, "which is ALLEGEDLY signed by Ted Berrigan, though I never believed it...It does say Ted; the book's in rough shape...Anyway, not knowing you, I thought of you...Do you want it?" He had bought it in Fayetteville and offered to send it to me for free. I said I'd love to have it. "I mean, there's no way (is there?) that TB signed a book BY Barbara Guest, but so the store claimed; it's where Matt Henriksen used to work. I bought it for something like $5, which only confirms the lie, but I guess the lie is also part of the legend, however much of the gutter, idle fantasy." I replied "It's totally possible that it is Ted's signature, but I wouldn't know anything without seeing it. He did sometimes sign his name in copies of others' books and signs his name in pages of his journals, etc, as a kind of performative framing. I don't know how it'd get to Fayetteville. But objects are wild, and you're right, hold the lie." This remains one of the best things that Twitter has ever allowed to happen.

It turns out that this copy of Guest's Poems is actually signed by Berrigan, which for books that came through Ted's possession isn't an uncommon occurrence. This book Berrigan gave as a gift, as his signature appears on the first blank page in pencil with a brief note, "Happy Birthday etc. Love, Ted." A bookmark for Dickson Street Bookshop where Shimoda bought the book is laid in with the note "Signed by Ted Berrigan." The handwriting, especially the large loop on the 'd' in "Ted," looks like other examples of Berrigan's handwriting from the early 1960s not long after he moved to New York City, so he likely bought (or stole) the book when it was new in 1962, soon before offering it as a gift to a friend. But why would such a rare New York School association copy of Guest's first book on a major press (only preceded by the Tibor de Nagy edition of The Location of Things) only cost $5? The book's personal history gets more complex on the inside of the back cover where in pencil the bookseller has written: "Note dated poem by Ted Berrigan and signed at front" with an arrow point to the left, where the book's final page would be. However, this note has been crossed out, underneath is written "STOLEN," and the book's final page, where the handwritten poem appeared, has been completely torn out. You can see the edge of the torn out page against the binding. It's terrible to be missing the handwritten, original Berrigan poem--likely a pre-The Sonnets work--and also to be missing the context given by the date. Ted regularly wrote in copies of books and magazines, sometimes adding one-off, original poems as he did here, but it's unclear who he gave this copy of Guest's book to. One would like to think Berrigan gave the book to Gerard Malanga on his birthday, who then reviewed this copy in the Spring 1965 issue of Kulchur magazine whose reviews section was then being edited by Berrigan. "In Barbara Guest," Malanga writes, "we have a poet of a sensitivity far removed from direct influences, a poet who has added fresh, even humorous, associations to her subject matter by a hallucinatory power of juxtaposition." (See the full review below.)

Regardless of who Berrigan actually presented the book to, it's exciting to wonder if the scant marginalia throughout the copy, mostly vertical lines along particular stanzas or X's by the titles of some poems, all in pencil like the dedication and signature, could be Berrigan's own. The last stanza in Guest's poem "Les Réalités" is one of the marked stanzas, and I can see how its sonic oddnesses and off-kilter play with symbolism would have appealed to Berrigan's sensibilities. Then first experimenting with amphetamines in the early 1960s, he might have also have found some humor in the lines "as this pharmacy / turns our desire into medicines."

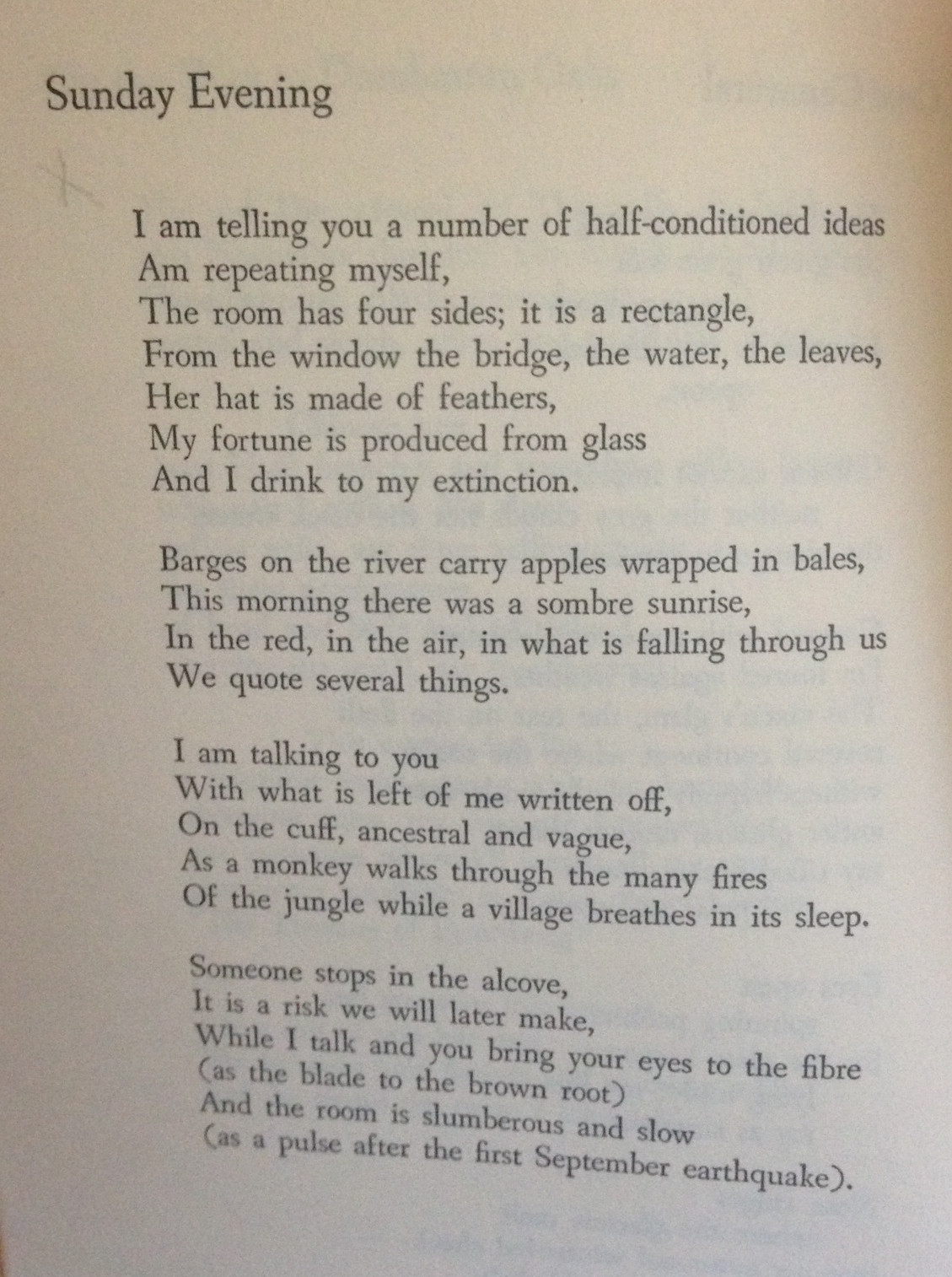

Guest's "Sunday Evening" is one of the few poems with an "X" marked by the title. Playing off Wallace Stevens's "Sunday Morning," the poem's colloquial, mysterious direct addresses, juxtapositions, formal repetitions, slightly bent images, and even the sonic texture of its vocabulary are all qualities Berrigan would have been attracted to. It's a little uncanny to read this poem with Berrigan in mind, as it starts to feel like a palimpsest for the moves and sounds in The Sonnets. Guest's lines "In the red, in the air, in what is falling through us / We quote several things" could act as an aesthetic description of Berrigan's collage of lineages in his poems. I'm not sure anyone has even attempted to read Berrigan and Guest in proximity, and I'm glad Shimoda sending me this book could lead to this sort of idiosyncratic reading. Books like this one, which are evidence of how oddly and magically books move through the world as these records of people, devotions, moments, thinking, care, lostness, and mystery, are exactly why I started writing the "Crystal Set" series in the first place. Objects are wild and attending to their wildness, acknowledging how their material residues refract and alter exchangeable narratives, can help us to reorient how we imagine the work of scholarship.

Read Erica Kaufman's excellent review of The Location of Things in Jacket2:

This dichotomy of inside/outside, voyeur/actor resonates throughout the book and continues to remind the reader that women do not have the luxury of occupying space in the same way men (her male contemporaries) do/did. In these early poems, we see the surfacing of Guest’s commitment to poetry that works as painting or architecture — poetry that demands the reader look at the thing in front of him/her and then let it teach them to occupy space, with one eye on object and the other on the gendered body that views it.

And listen to the May 1984 recording on PennSound that include's Guest reading "Sunday Evening.

Gerard Malanga's review of Poems by Barbara Guest in Kulchur 17 (Spring 1965)