Circus Nerves by Kenward Elmslie (Black Sparrow Press, 1971). Perfect bound with cover image by Joe Brainard. This one no. 66 of 200 hardcover copies signed by Elmslie.

I bought this copy of Circus Nerves last summer at The Captain's Bookshelf in Asheville, North Carolina--one of my favorite bookstores--along with the 1968 Something Else Press edition of Geography and Plays by Gertrude Stein and the 1948 first American edition of The Moment and Other Essays by Virginia Woolf. I've always loved this Brainard cover image--the subtle sexiness of the offset torso, the primary color bonanza of tattoo parlor staple images arranged into an almost occult figuration. The exaggerated, cartoonish curves of the female nude contrast with the realistic but anonymous nude (we assume) male body it's printed onto. These nonverbal symbols of mid-century Americana and heterosexual masculinity are tweaked into a celebratory, queer portrait of the male body as canvas and subject, as art itself. I think my grandfather, a World War II veteran, might have actually had the exact same bald eagle tattoo on his arm. Brainard made a series of works featuring tattoos throughout the early 1970s--one was featured on the cover of Artforum in 2001--and tattoos of anchors and butterflies would appear throughout his work. Tattoos make sense as Pop art images--endlessly repeated and recycled bodily ads of the cultural imagination--and Brainard handles them with his quintessential humor and vulnerability. Even the gorgeously typeset title page anticipates Elmslie's cross-genre American imagination. It's all energy, performance, and attraction--a good visual primer for Elmslie's buoyant, charming, and powerfully weird lyrical gymnastics in Circus Nerves.

I say "weird" with the greatest adoration. Reading the first poem in Circus Nerves, "Ancestor Worship," in which "[t]he young master / coughed himself inside out one day, and bravo! // rematerialized as a red cactus" and "grandfather sat naked and cooled, / singing of traffic organized like a factory, rashly," you'd be forgiven for not noticing that the poem is, in one way of describing it, about giant insects eating the world. Whether or not you remember when the monstrous "[a]nts chomped at / the jigsaw puzzles, ground with their hideous mandibles // treey landscapes and Venices at sunset," a mishmashed environment of American surrealism cum sci-fi European classicism, there's something to enjoy and wistfully read through at every turn. The poems' scenes and sources, like the work of Elmslie's close New York School friends, are constantly shifting and unexpectedly inclusive. One of my favorite sets of lines in the book are from the end of "Ashtray Offer" where while working Elmslie and Brainard are listening to the 1970 song "Contact High" by Ike & Tina Turner: "'Contact High' is a lovable old new tune / collages everywhere and no oasis // Joe hunts for bones / and me: black stones." Or the incredible "Nov 25" with its inventory of New York School names amidst the media-rich atrocities of the Vietnam War, which ends: "we'll wrap our bombed friends in palm fronds // and become a singing people (did you enjoy your turkey) / hey we are a singing people (the wing part tasted metallic)." Like Kenneth Koch's "The Circus" from his 1962 book Thank You and Other Poems, to whom Circus Nerves is dedicated, Elmslie stages these grand processions of lines--a parade of vibrant, glitter-spazzing nouns and ricocheting narratives--that, mixed with a little cute abjection shaped into the comedy of sonic slippage, fete and disorient a reader into a sublime, rogue dreaminess. Just working to write these descriptions of Elmslie's poem is a joy. His work amplifies all the bent wonder that serious thinking requires.

Always, though, there's an elegiac lostness tied into the circuits of daily affect. Take his "Entry (for Mary Clow)," in which despite all the fun of Anne Waldman's birthday the news of a friend's passing spurs the observation that "Anne'll never again see 24." Aware of his "Taurus Depression," he leaves the celebration to lock himself in his room where "rock throbs blast through floor." Alone, he inventories the events of the day in uncharacteristically spare fashion, almost a darker version of Berrigan's "10 Things I Do Everyday": "morning news / answer phone / friend dead // feed face / head for heat / sweat and fret // see movie / grieve in the dark / in middle: leave." These are the nerves in Elmslie's circus, the living connections but also the raw, untethered ends. The last poem in Circus Nerves, "First Frost," which addresses the death of Frank O'Hara, is a moving example of the tender brittleness layered in Elmslie's imaginative vision. Beginning in what could be an idyllic landscape of beauty and comfort, the scene triggers Elmslie's memory of a few years before in 1966 when "that summer stopped / fragments and remnants" and he "returned to NYC / scared I'd wake up in DOA City / holocaust: no Frank O'Hara // audible chasm: no Frank O'Hara." Colored by the rhetoric of the ongoing Vietnam War, Elmslie imagines New York City transforming into "Dead On Arrival" City, a national, political, and aesthetic "holocaust" in which a whole world, the world with his dear friend O'Hara in it, is annihilated. The "fragments and remnants" of the rest of the poem, also the "fragments and remnants" of O'Hara left with the living, like "snatches of his voice in certain intonations," are housed in these clean-looking staggered tercets that hold up the wobbly oscillation between pieces. Like the simultaneously "frozen" and "spewing" milkweed, these pieces hold together as they fall and separate, gutted by the absence that animates their movement, that "audible chasm: no Frank O'Hara." I can't get over the last stanza with its intricate loveliness and the grief that looks to earlier lines for an almost pleading sequence of isolated repetitions. Referring to John Giorno's Dial-a-Poem service that started in 1968, Elmslie is perhaps referring to O'Hara's contributions to the project, these recordings of "Ode to Joy" and "To Hell With It," the former of which repeats the iconic line "No more dying" and the of latter which is prefaced by O'Hara's explanation that "The occasion of the poem is not that two friends of mine died but obviously it was in the back of my mind if not the front when I wrote it, and I think that probably after the initial shock death makes me angrier rather than sadder as an event." Though the first Dial-a-Poem LP wouldn't be released until a year after Circus Nerves was published, Elmslie is already listening to "Frank sing."

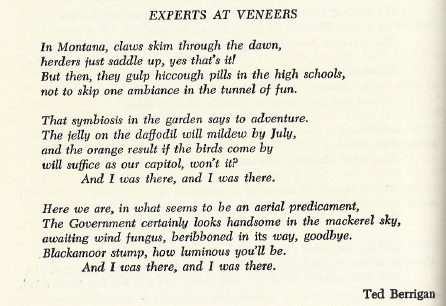

Some of the poems in Circus Nerves were first published in Power Plant Poems, one of the early run of books from Ted Berrigan's "C" Press. Published in 1967, Power Plant Poems includes this awesome portrait of Elmslie in sunglasses by Brainard. Ted actually appears in Circus Nerves in the poem "Awake on March 27th," a description of waking up before his guests one morning at his home in Calais, Vermont. Before describing Brainard, his longtime partner, sick with the flu, being as hot as "a jalopy in the tropics," the poem begins: "my thoughts turn up / always the first one up around here / Ted's god-fearing farmer red Hi Folks beard / with its growth of unabashed pseudo-pubic hair / mebbe's scratching kinkily against the clean maiden / sheets as pellets of old speed sift through his system / asleep on top floor." While not clearly the most flattering portraiture, it's absolutely Ted, and I love the description of his "god-fearing farmer red Hi Folks beard." He and Ted were close friends. In the Autumn 1965 issue of Kulchur, Berrigan had reviewed Elmslie's 1961 pamphlet Pavilions, published by Tibor de Nagy. A great example of the wit and intelligence of Berrigan's prose in his early reviews, I've always adored the anecdote (apocryphal?) from Tom Veitch about the Elmslie altar. Here is the complete review transcribed:

Kenward Elmslie is the least well-known of that group of poets mis- but aplty-named (by John Myers & Don Allen) "The New York School," whose roll (I think) would include John Ashbery, Kenneth Koch, James Schuyler, Frank O'Hara, Barbara Guest, Bill Berkson, and not Edward Field. (And Kenward Elmslie.) At the moment I'm not at librerty to reveal its location.

(Also, as a matter of fact, James Schuyler is making a strong bid for Kenward's title. However, with regards to both these writers, an underground group of young Turks seems determined to "get the manuscripts" from them and "plagiarize their works!")

I know that reading Kenward Elmslie's poems has had a strong effect on my own writing. For one thing, he has made me very aware of individual words, their sweet eccentricity. For another, and most important to me, the way his poems ARE (i.e. 'take place') Right Now is tremendously exciting. He is able to include a kind of daylight nostalgia in his poems without sacrificing any of the present to the past, a very sexy and useful trick in making right now be Right Now. He is a very personal poet though he tempts us often to forget it. Like Ashbery and Koch and O'Hara (each in his different manner) Elmslie is an American poet with an absolutely non-UnAmerian style (voice). Offhand I would guess that he owes less to Apollinaire than his schoolmates, and perhaps more to hardcore Surrealism. (That's a pretty unbelievable sentence, wonder who I've been reading?) As a matter of fact, Kenward Elmslie's poetry is almost nothing like Surrealism. I remember when I first met Tom Veitch, about four years ago; one day he noticed my copy of Pavilions and he told me that some friends of his at Columbia had built an altar to Kenward Elmslie in their room to pray to during exams. It wasn't so much his poems, although they liked them a lot, it was his name: Kenward Elmslie. They thought that that was really a great name. Prayed to it every day.

[Berrigan reproduces in full Elmslie's poem "The Dustbowl" as published in Art & Literature #1]

The Elmslie poem Ted references at the end of his review.

Lately Kenward Elmslie's poems have been appearing in C, in Aram Saroyan's Lines magazine, in Mother magazine and Arts & Literature; and for those interested, he has had work in Gerrit Lansing's Set, in Locus Solus #'s 2, 3, and 5, in The Hasty Papers and in A New Folder, just to mention a few. He also did the libretto for the Opera Lizzie Borden which premiered in March at the New York City Center. And he and Joe Brainard have collaborated on a beautiful Baby Book (available at 8th Street Bkshop) which I presume will be reviewed in this magazine sometime. Of the poems in magazines, the one that shouldn't be missed is Elmslie's long, beautiful and very major (what the mans) poem, "The Champ," in C #10. Now to end let me quote the poem containing the great line I've read in anything, anywhere.

If you're not familiar with Elmslie's work, an issue at least since Berrigan wrote his review in 1965, I recommend reading through his Routine Disruptions: Selected Poems & Lyrics published in 1998 by Coffee House and likely easy to find. In a review of Routine Disruptions, Alice Notley begins with this incredible description:

Contemplating writing this review of Routine Disruptions: Selected Poems & Lyrics by Kenward Elmslie -- an excellent collection -- I've been unable to dislodge a picture from my mind. It is of Elmslie during a reading several years ago, with a large "hat" on, made by an artist, that used as its primary image a large brassiere. A man reading poetry with a brassiere on his head! This is an icon, for me, of Elmslie's work, its wild funniness, theatricality, brazenness, its love of art and objects. Cleanly designed strange or beautiful objects, as in poems, as poems, words as objects, but . . . this is not a doctrine, and the face below the bra-hat, Kenward Elmslie's pleased bemused own, never disappears.

Says Michael Silverblatt in the introduction to the recent print by Song Cave of Elmslie's The Orchid Stories:

Kenward Elmslie’s perverse, scabrous, gorgeous poetry and prose have astonished his fans for over fifty years—decades during which he remained the pride of small presses, the happy secret of cognoscenti—but it is safe to say that the vast audience his work deserves doesn’t know what it’s missing. He’s the most extravagant, and extravagantly overlooked, poet in America.

Says John Yau in his review of The Orchid Stories, "The Great Kenward," in the perfectly frank prose that makes Yau's writing the best:

It’s great that Song Cave has brought The Orchid Stories back into print. Elmslie is the perfect writer to begin reading in an age that worships profligacy and the collecting of luxury items and art trophies. As in the sentence about coffee that I just cited, he can morph from a realist opening shot (“One finishes one’s coffee) to a cartoon image at the end (“like an old-fashioned baby spoon”) while passing through a moment of extreme, self-destructive violence (“one hacks it with one’s spoon…). Next to Elmslie’s sentence, Jeff Koons’ “Balloon Dog” looks like what it is, expensive contrivance.

But really, one should start by watching this selection from the documentary Poetry in Motion, produced by Ron Mann in 1981. Of course, Elmslie is a celebrated lyricist and writer for musicals, including The Grass Harp, a musical adaptation of Truman Capote's novel that was first staged in 1971, the same year Circus Nerves and another poetry book, Motor Disturbance, were published. Watching this video and listening to this recording of two additional songs from an undated performance at The Poetry Project, I'm imagining "Prairie Home Companion" joyfully erased from our world and in its place instead we have Kenward Elmslie hosting a public radio variety show called "The Tunnel of Fuzz" or "Unshaven Mystery Bomb" or "The Violin Rallies." I love Elmslie's poems and hope you do, too.