It’s not every day that I have the opportunity to hop on the radio to talk about teaching the archives, let alone to curate a set list of Ted Berrigan-centric New York School-related songs, but that’s exactly what Lost in the Stacks, the research library rock’n’roll radio show at Georgia Tech’s WREK asked me to do for our episode “Teaching the Archives.” It was so fun to be able to talk about the Raymond Danowski Poetry Library at Emory University and Berrigan’s poetry in such a vivid, energetic medium. Lost in the Stacks describes itself as “the original research-library rock'n'roll radio show! Broadcasting on WREK Atlanta, each show features an hour of music, interviews, and library talk united by a common theme.” It’s an incredible show with episodes about open access issues, citizen archiving, exciting original research, all things library culture, and refreshing perspectives on the work of libraries, archives, and the folks who make them run—plus great music.

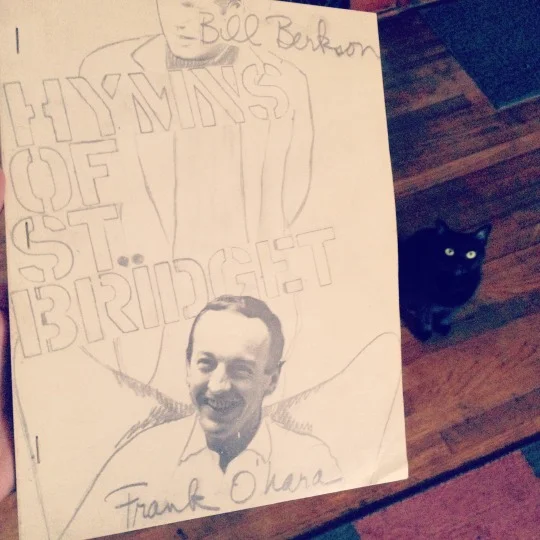

It was a pleasure to talk with hosts Charlie Bennett, Public Engagement Librarian, and Wendy Hagenmaier, Digital Collections Archivist, and to be able to co-produce the episode alongside them. In our conversation, we talk about my use of archival materials from Emory’s Rose Library—particularly from the Raymond Danowski Poetry Library—in my first-year writing courses at Georgia Tech and as visiting faculty at Emory, encouraging students to do their own original research at the Rose Library, the joy of the “material oomph,” my scholarship on Ted Berrigan and Alice Notley, the New York School’s overlap with punk and rock music on the Lower East Side, and the incredible pedagogical wealth of the Danowski Library. And by the way, early in the episode I mention a student project on the band Television’s connections to the New York School of poets—the same band from which the intro/outro song of Lost in the Stacks is sampled—and that completed project, “Television: Where Punk and Poetry Meet,” which utilizes copies of the rare magazine Genesis Grasp from the Danowski Poetry Library to showcase the early aesthetic influence of the New York School on Richard Hell and Tom Verlaine—is available here.

A few quick annotations on my choices for the playlist for this episode that aren’t addressed directly in our conversation:

“Early Mornin’ Rain” by Bob Dylan: In the Early Morning Rain is the title of Ted Berrigan’s book of poems published in 1970 by Cape Goliard Press/Grossman.

“California Dreaming” by The Mamas and the Papas: In his iconic “Red Shift,” Berrigan writes at a particularly dramatic momentum-turning point in the poem “There’s a song, ‘California Dreaming,’ but no, I won’t do that.”

“People Who Died” by Jim Carroll: Carroll was a close friend of Berrigan, Notley, and many other New York School poets. Carroll’s infamous The Basketball Diaries was first published by New York School small press United Artists. “People Who Died” is also a poem by Ted Berrigan.

You can listen to the full episode of “Teaching the Archives” here.

The vinyl and music stacks at WREK’s own riotous archive.