White Country by Peter Schjeldahl (Corinth Books, 1968)—48 pages, perfect bound. Designed by Joan Wilentz and printed at The Profile Press in New York City with cover by George Schneeman.

I bought this copy of White Country in May 2014 at The Haunted Bookshop in Iowa City. Carrie and I were driving from Minneapolis to Tallahassee and had stopped to see Jared. We ate fiddleheads, buried a clay book in the forest, and played pool with Sarah at the Fox Head.

I thought of the book yesterday while reading Schjeldahl’s essay “The Art of Dying” in the New Yorker, his intimate, funny, and deeply moving reflection on the approach to the end of his own life. The phrase “reflection on the approach”—how to look back at something that is your future?—is indicative of the complexity of Schjeldahl’s essay. He builds an idea of death as a common space, something we’ve been variously sharing with those who are still here, those who are gone, and ourselves. His struggles with alcoholism, relationships, family, career, and art are told through a series of vignettes, sometimes witty and aphoristic, sometimes troubling and painful. Schjeldahl frames the essay around his inability to feel he was genuinely capable of writing about his own life. “I could never sustain an expedient ‘I’ for more than a paragraph,” his writes. Dying from lung cancer, he finally writes right into himself, and one learns some interesting things about Schjeldahl’s life, not the least of which is that he and his wife, Brooke, own a mini-golf course in the Catskills. For someone whose poetry and art writing career bloomed out of the lush incongruities of the New York School, this is a strangely fitting and noble image. I also found the following to be exceedingly helpful in the practice of looking: “I retain, but suspend, my personal taste to deal with the panoply of the art I see. I have a trick for doing justice to an uncongenial work: ‘What would I like about this if I liked it?’ I may come around; I may not.”

But what made me think of White Country reading “The Art of Dying” is how Schjeldahl describes his relationship with his poetry and poets: “[This essay is} the first writing ‘for myself’ that I’ve done in about thirty years, since I gave up on poetry (or poetry gave up on me) because I didn’t know what a poem was any longer and had severed or sabotaged all my connections to the poetry world.” There’s both resentment and an entrenched sense of his own perceived shortcomings here, but also no regret or meanness. It’s thick. I don’t get the sense that the audience Schjeldahl imagined for this essay is familiar with him as a poet. As he writes, “Lee Crabtree. Jairus Lincoln. Jeff Giles. You don’t know about them. They were friends of mine who died young.” I didn’t know about Jarius Lincoln—a friend of Schjeldahl’s at Carleton College in Northfield, Minnesota—but I do know about Lee Crabtree, of The Fugs, and Jeff Giles, a co-editor of Mother magazine. It makes sense that Schjeldahl says his readers won’t recognize these names—he’s known for his impressive career as an art critic, and how would most readers know about The Fugs or an obscure small magazine? While Schjeldahl doesn’t encourage us to think much of his poetry, his essay made me want to immediately re-read White Country and to make the case for the value of Schjeldahl’s work as a poet as well as for his important editorial work and writings about the New York School.

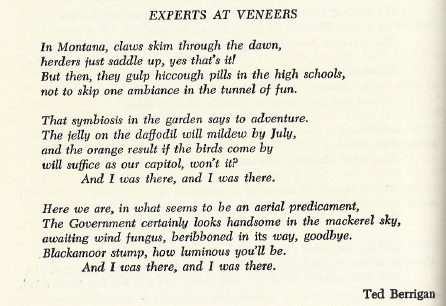

Published by Corinth Books—run by Ted and Joan Wilentz out of the iconic Eighth Street Book Shop and one of the most important alternative press of the 1950s and 60s—White Country is a slim, austere volume of poems that crosses influences from Schjeldahl’s New York School peers—there are poems echoing Ashbery, Koch, and Berrigan, in particular—along with a range of other influences that Schjeldahl collages into the work. The two major parts of the book are “The Paris Sonnets,” written in 1964 during he and his first wife Linda’s year living in Paris, and the long poem “The Page of Instructions,” a distinctly Ashberian labyrinth of soft metaphysical crises and ekphrastic digressions that spiral and wonderfully consume themselves. As he writes toward the end of the poem, “the catastrophically distended context puts all minor weirdness / Out of sight,” punctuating the metapoetic first line with ‘60s-tinged slang that doubles as a critique of looking at visual media, the poem’s always-slipping-away focus. “The Paris Sonnets” is imitative of Ted Berrigan’s The Sonnets, to whom the sequence of 20 sonnets is dedicated, but openly so, written in the year The Sonnets was first published by “C” Press and marked by the same kinds of collaged repetitions of lines as Berrigan’s poems. “The Paris Sonnets” even uses a few small lines that, as far as I can tell, Schjeldahl lifted from Berrigan and not, as is usually the case, the other way around (although I could be wrong!). On a more personal level, what’s most memorable to me about “The Paris Sonnets” is that it contains the only reference in a poem to Akron, Ohio, the city where I'm from, other than Hart Crane's "Porphyro in Akron." It's a great delight to come across that word—Akron—in a poem: “You have many friends in New York City and in Akron / Friends flock from every village to catch your tears.” I love how the Midwest clings to the New York School in its odd corners. I think the last three lines of Crane’s poem resonate with Schjeldahl’s sense of interiority and privacy: “You ought, really, to try to sleep, / Even though, in this town, poetry's a / Bedroom occupation.”

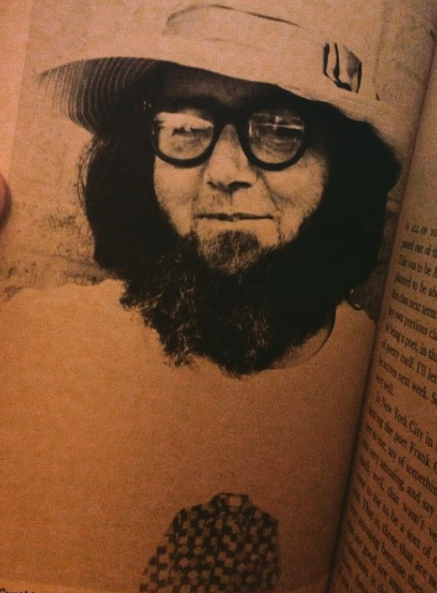

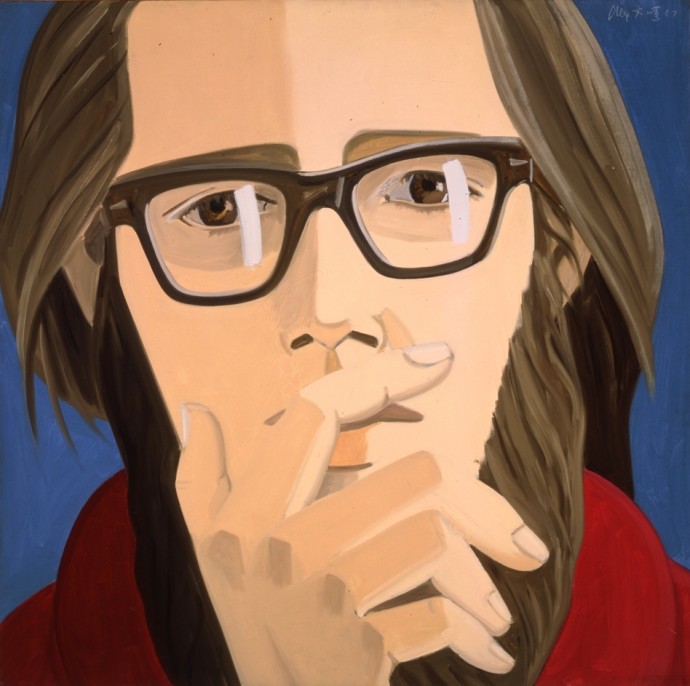

Schjeldahl’s contributor photo from An Anthology of New York Poets (1970)

What’s most notable about White Country are the poems’ tense self-consciousness. There is an angst and antsyness to these poems that have them wound up around a performative but shy first-person. One senses an intimated speaker, someone sticking to the background to observe. These poems don’t fly off into sonorous juxtapositions (like Berrigan) or surrealistic images (like Padgett), although both poets are deeply a part of Schjeldahl’s work. It sometimes appears as a flat existential dread, like in “Blue” where he writes, “What’ll we do if we can’t be perfect? / We’ll die. I’m only joking,” and sometimes as self-deprecation, like in “Here I Am”—“I’d rather be unbearable than empty.” In “Pounds,” Schjeldahl offers what sounds like a description of writing poetry—”I start thinking, then think / Sideways until it annihilates thought”—that is simultaneously liberating and terrifying for its desire to get out of the confines of the first-person. Death and loss linger across the book.

But there’s also a significant amount of joyous strangeness in White Country, especially when Schjeldahl experiments with repetition and variation in ways that are completely his own. Take these lines from “Radio in the Hills”—”And so he lays the music open. // As a pomegranate in the rich garden of an open / Book of analogies.” The image is self-reflexive and mysterious, lush and musical, but the repetition of “open” at the end of two consecutive lines is so wonderfully odd—like an imperative chant, “open, open,” is running underneath the poem. This happens again in the book’s title poem, “White Country,” where the word “gold” repeats in each of the first five lines and then “slogan” appears in three of the last six lines. These villanelle-like cuts and splices work with the tenseness of Schjeldahl’s poems, distorting and amplifying the affect beyond the personal contexts that haunt the poems’ edges. There are also just some great lines in this book. I love the end of “Soft Letter”: “The bland bias of the room is cradled / In the blood; and “love” is the code by which / Bovinely quizzical, we circumnavigate the bulk we / Incidentally create continuously, with just / Occasionally a wan evacuation, and now and then / The fascinations of a hand.” His poems are also really funny, as the recordings of his readings make clear. His distinct, nasally voice paired with what he calls the “gentle malice” of his poems adds a comic, cartoonish flair to his performances.

Of course, it’s also worth noting that White Country takes aim at Robert Lowell—twice!—in the satirical “Life Studies,” a series of Kochian vignettes that parody the seriousness of lyrically contemplating narrative moments as metaphors—and in the opening lines of the poem “To the National Arts Council” where Schjeldahl writes, “Hello America let’s tell the truth! / Robert Lowell is the least distinguished poet alive. / And that’s just a sample / Of what it’s going to be like now that us poets are in charge.” Blustery and rhetorically performative, Schjeldahl cuts into the sanctimonious privilege offered to the era’s most well-known and legible poets. It’s like Koch’s “Fresh Air,” but Schjeldahl goes right at Lowell by name. “Life Studies” and “To the National Arts Council” are two of the ten poems by Schjeldahl collected in An Anthology of New York Poets edited by David Shapiro and Ron Padgett. Oddly enough, Marjorie Perloff uses this anthology as a punching bag to begin her 1973 omnibus review of new poetry in Contemporary Literature, returning fire at Schjeldahl by using the lines quoted above from “To the National Arts Council” as the epigraph to her review. She begins:

These lines from Peter Schjeldahl's "To the National Arts Council" may not have any particular literary distinction, but I find them peculiarly prophetic of the new turn poetry is taking in the seventies. Reading the thirty-odd poets under review here, one is especially struck by the growing cult of Frank O'Hara, whose disciples, the former New York underground, once associated only with such coterie periodicals as Mother, Locus Solus, and Angel Hair, have begun to take over the literary scene.

It’s funny that Perloff singles out Schjeldahl (and his magazine, Mother) as representative of her “scummy acolyte” portrait of the New York School, which she sees as losing sight of itself in the wake of O’Hara’s death. Perloff continues: “Robert Lowell, with his strong sense of poetic convention, historical tradition, and the niceties of prosody, is viewed by a New York anti-poet like Peter Schjeldahl as the Enemy.” She’s not wrong, but she’s not right either.

As Schjeldahl’s first book, White Country is a quintessential “second generation” New York School text. His editing of Mother in Northfield and New York City in the 1960s—with covers by Joe Brainard, George Schneeman, and Mike Goldberg—was also central to the aesthetic moment. Mother saw the first publication of Berrigan’s “Tambourine Life” and his collaged “Interview with John Cage” (which, without the judges knowing it wasn’t a real interview, resulted in a prize and awkward phone call with George Plimpton), and printed poems by other first and second generation New York School poets alongside work by Robert Creeley, collaborations by William Burroughs and Brion Gysin, and portraits by painter Alice Neel. It was one of the most important little magazines of the era. Issues #3 through #8, spanning from 1964 to 1967, are now available in digital facsimile editions at the Independent Voices open access collection.

From left to right: John Ashbery, Peter Schjeldahl, Gerard Malanga, Dick Gallup, Ted Berrigan; circa 1964.

Even if Schjeldahl is slightly self-conscious about his role within the poetries of the New York School, as “The Art of Dying” suggests, the evidence proves otherwise. Consider Schjeldahl’s incredible obituary essay for Frank O’Hara in The Village Voice (which was just republished online in June); his appearance in An Anthology of New York Poets (1970) in which Schjeldahl’s poems have the distinct honor of appearing directly before O’Hara’s; Alex Katz’s inclusion of Schjeldahl in his iconic Face of the Poet series in 1978 (accompanied by his wonderfully funny poem “Ars”); Schjeldahl’s friendship and collaborations with Schneeman (“George changed me in 1965, in Italy, by showing me how to use art: take it to the heart”); and his support and proximity to some of the best poets and artists of the New York School, let alone of the second half of the twentieth century. There’s a terrific series of photographs by Steven Shore of what looks like an after-party for a John Ashbery reading, likely in 1964, and it’s no surprise to see Schjeldahl alongside Gerard Malanga, Dick Gallup, and Ted Berrigan talking with Ashbery. He was completely part of that scene, that world, and still is, through all its still ongoing afterlives.

Peter and I corresponded briefly in early 2016 after I met his daughter Ada. She had just published her great book St. Marks Is Dead: The Many Lives of America’s Hippest Street, which I wrote about for ArtsATL, and she suggested I reach out to her father about my scholarship on the New York School. We emailed just a couple of times, but he was generous and refreshingly straight forward. I sent him a link to my recent essay on Berrigan’s writing for ARTnews. “Ada told me of her pleasant encounter with you,” he wrote, “And now I've enjoyed your essay on Ted's art writing.” That second sentence has a quirky angle to it, the way that it’s set in time through the use of the present perfect tense, that perhaps shows something about Schjeldahl’s unique attention to how sentences work, even how the act of reading works. “I think off and on about people I love, but I think about writing all the time.” I’m glad Peter is still here and will be, through things like this, and in the poems, too. Alongside John Yau and Carter Ratcliff, Schjeldahl is one of the last great living poet-critics of the New York School.

Schjeldahl’s later books of poetry are An Adventure of the Thought Police (Ferry Press, 1971—with covers by Joe Brainard), Dreams (Angel Hair, 1973), Since 1964: New & Selected Poems (Sun, 1978) and The Brute (Little Caesar Press, 1981).

An amazing, entertaining video recording of Schjeldahl reading at the Maryland Institute College of Art in 1983 is available to watch here and his recent reading with Major Jackson at Dia from March 2019 is available here.

Schjeldahl lights a cigarette before reading his poem “Dear Profession of Art Writing” at the Maryland Institute College of Art in 1983.

“I associate George with brilliance of mind that hovers weightlessly, either no big deal or no deal at all. It doesn’t go anywhere. (Happiness is wanting what you have.) I stare at his works in my possession, and my heart hangs fire. Words flop.”

—Schjeldahl, “George Inside” from Painter Among Poets: The Collaborative Art of George Schneeman

Peter Schjeldahl from Face of the Poet (1978) by Alex Katz