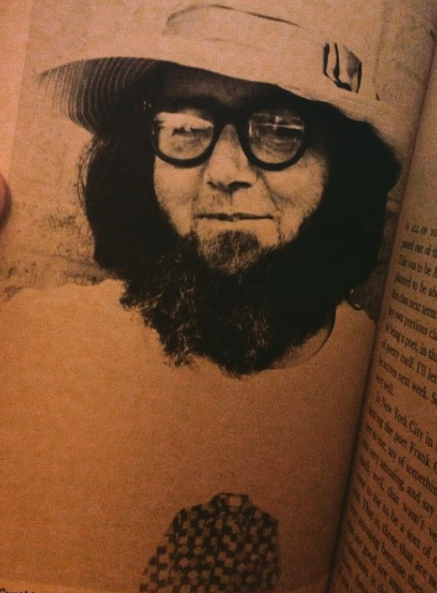

Berrigan wearing a shirt featuring a George Schneeman print

A couple of years ago I was writing an essay on Ted Berrigan's little-known art writing for ARTnews, a lively, intense yet brief span of work from 1965 to 1966 in which Berrigan reviewed over 100 gallery exhibitions and produced a handful of feature articles. That essay, "The Pollock Streets: Ted Berrgan's Art Writing," was published in Fanzine as Part 1 and Part 2. Berrigan's devotion to art writing was a way to continue his own self-education in art and a way to stand alongside while insisting on a difference between himself and first generation poet-art critics like Ashbery, O'Hara, and Schuyler whose art criticism, unlike Berrigan's, is quite well known. I first found out about Ted's work for ARTnews reading his 1972 interview with Barry Alpert in Talking in Tranquility, and was a little stunned to find the information so out in the open, in a book published over 25 years ago. Finding Ted's contributions to the magazine was another layer of unexpected pleasure -- I just went to my university library where every issue of ARTnews had been bound and conspicuously shelved away. Sure enough, Berrigan's contributions were brimming in the mid-60s. While Ted didn't contribute to ARTnews after December 1966, he did publish one last piece of art writing in Art in America in March 1980 on his long-time friend George Schneeman. As Notley describes in "A Note on Ted and George" from A Painter Among Poets: The Collaborative Art of George Schneeman, Berrigan and Schneeman's friendship was full of a thick reciprocity organized around shared aesthetic spaces, a way to live. Notley writes:

"Ted was always collaborating with George, even when they weren't officially collaborating. And I think George was influenced in a general way by Ted's individualistic, ugly line (as evidenced in his signature) and by his complete assurance that the ugly was artistic and that he, Ted, was an artist too. (I can hear George telling me Ted's signature wasn't ugly, and I guess it wasn't.) When George says he is "unhandling" paint, in my interview with him in 1977 [originally published in the Chicago-based magazine Brilliant Corners and included in Notley's book Waltzing Matilda], I think he is voicing an esthetic partly developed with Ted. Obviously Ted and George shared a sense of humor, but they also shared a sense of sentiment, and something like an ethical tension. To what extent does one honor society's code (thus producing sentiment), and to do what extent does one go against these codes in order to be an artist?"

Below is the complete article, "George Schneeman at Holly Solomon," which is Berrigan's last published piece of art criticism. It's fitting that it's on Schneeman, whose paintings of Ted and their collaborations together are so wonderfully descriptive of the lives they shared. One will notice that Ted uses the same phrase, "unhandling," to describe Schneeman's use of paint, evidence of his ongoing attention to the conversation they had all been building together. And it would be wrong not to point out that the last line in this review, which describes a fresco featuring Ted, "the colors are serious – something portentous is at stake," directly echos these lines from Sonnet I in The Sonnets: "Still they mean something. For the dance / And the architecture. / Weave among incidents / May be portentous to him." Up in the air, a little sonorous wonder.

from Art in America Vol. 68, No. 3 (March 1980), pg 118

GEORGE SCHNEEMAN AT HOLLY SOLOMON

With his third show of frescoes in three years, Schneeman’s place among the most accomplished painters now coming to the fore makes itself obvious. The 23 paintings included were mostly small, though by no means diminutive, and their variety, arrived at through formal means (size, shape, dispersal of subject matter) made walking into the gallery a great pleasure.

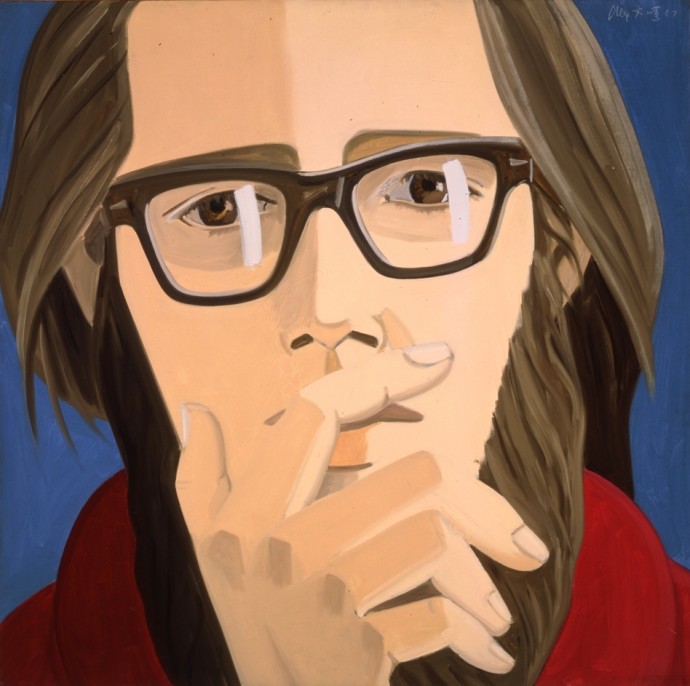

Schneeman lived with his family in Italy, near Siena, from 1959 to 1966, and did some fresco painting then. During succeeding years in New York he painted mostly figures, on fairly large canvases in acrylic – friends and family both clothed and nude. These remain marvelous pictures, done in his characteristic manner of “un-handling” the paint (no brushstroke virtuosity), with drawing and painting often taken to mean the same thing. Highly admired by a few, this early work nevertheless brought the artist little of the notice or success that should have been his.

Schneeman’s first show of frescoes, three years ago, consisted of some 75 small examples, each 7 by 9 includes, mounted on 2 1/2-inch-thick cinderblocks. They were paintings of flannel lumberjack shirts in three-color plaids, flattened on wire hangers and depicted dead center on an eggshell white background. The show was a success, all the paintings were sold, and reviews were admiring. His show last year consisted of over 60 more frescoes, similar in size but of heads this time, and while loved his admirers, it was only a modest success. (Who wants a monumental object, that cinderblock, with the face of someone you don’t even know on it?)

This most recent show was a knockout from any point of view. There were four of the familiar shirts, on silver hangers this time and done in relief. They are perfect. The four window paintings, a shade larger than the shirts (9 by 8 inches), are almost equally accomplished, their kitchen-window curtains – also done in relief – opening out onto remembered Tuscan landscapes that the dazzling white window mullions divide into quadrants.

Also included were four landscapes, all complete winners. Three are rectangular, one recapitulating the famous Veneziano John the Baptist landscape, minus the saint. The fourth, my candidate for most charming picture in the show, is round, mounted on a rectangular white base, and slightly recessed so as to emphasize its distance from the viewer.

Finally there are the figure pieces, which are not portraits per se, but people sitting for paintings. Two such single-figure works are based on Piero di Cosimo’s Profile of a Young Woman. The first, Anita is of a ripe beauty; the painting is round and has been given a white mounting resembling a Duchamp rotorelief. It is all innocence and light, truly delectable. The second, Alice, is rectangular and dark, with storm clouds curling behind the woman’s dark, chopped hair. Her knowing but unspeaking face is paired with a sensual, womanly body that is all about earth and outdoors. A third painting, Britta, of an individual against landscape is one of the show’s real standouts. In front of a rough Tuscan landscape, in profile, is an implacably made-up European (German) head, with red hair tight across the forehead, and red lips.

The highlight of the show was a painting of the kind referred to in the quattrocento talk as a “Sacra Conversazione.” Three Figures/Landscape gives us three men in the foreground, the figure on the left turned into the picture, the figure on the right (who, I ought to point out, is myself) turned slightly outward. Behind them a third figure wearing a straw hat looks straight at you, smiling in a blissful awareness of stage center. The artist has used landscape to pull the picture together, and also to disguise the seams (Frescoes dry so quickly – within three hours or less – that only one figure can be painted a day. Next day, or session, more plaster is applied, and another figure may be added, etc.) Two of the figures have Hawaiian shirts on. The sky is a triumph, the figures are poised in attitudes befitting their countenances, the colors are serious – something portentous is at stake.

-- Ted Berrigan