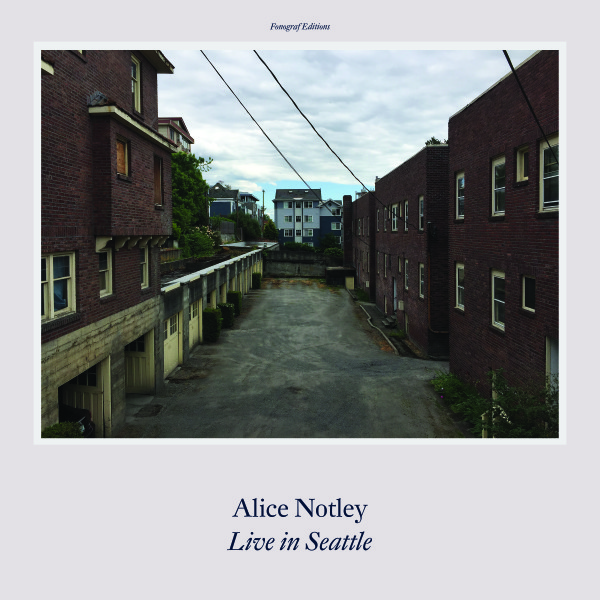

My interview with Alice Notley, published on the occasion of the release of the vinyl LP Live in Seattle (Fonograf Editions), was recently published by the Poetry Society of America and can be read here. The interview is an edited selection from an hour and a half phone conversation between Atlanta and Paris that took place on September 16, 2017. Below are a few portions of our conversation that didn't make into the final piece. These excerpts are unedited and show more of the range of our conversation, including Notley's lifelong visual art practice, links to Chicago (where her and Berrigan lived in the early 1970s), relationship with artist George Schneeman, and what her collected poems might look like. Though not included in the published interview, these pieces are equally irreducible.

***

Nick Sturm: I spend a lot of time with your early work because the things that it does are so various from the things that your work has done since The Descent of Alette. And spending time with that work has changed the way I think about these different processes of writing. Whether it’s “Endless Day,” “September’s Book,” “Jack Would Speak Through the Imperfect Medium of Alice” – they’re so funny. Your work has always been funny. Like I think of the “Postcard” poem in Waltzing Matilda that begins “Dear Fuckface” and ends “Love Bubbles” that’s so blasphemous and fun and pleasurable. What I'm asking is: I wonder if you’ve ever had an experience like this--creating effects in your poems--where it doesn’t feel as if you’re writing but more like you’re arranging?

Alice Notley: I’m not that kind of writer. Other people are, but no, I write. I write and it comes out of me. I don’t arrange things. I don’t take things from different places and stitch them together or anything like that. Ted sometimes spoke as if he did that. But I’ve never done it. I have a voice coming into me and then out of me. A lot of time it’s somebody else’s voice. Like in the “Postcard” poem they’re all my voices but in each one I’m saying well I’m this person writing to this, although it’s all the same person. Then at the end the last one is “Dear Francis” and its signed Alice and at that point I have arrived at my voice. I was asked to discuss this in a class taught by Tom Devaney last November and then he asked me if Francis was Francis Waldman, Anne’s mother, and I said, “No, it’s Frank O’Hara!” and he started crying. [laughs] I said, “You’re crying!” and he didn’t know what to say.

***

Nick: These are little tangential things, but asking you about some important things that you’ve done that haven’t often been talked about. For example, your writing’s relationship to painting, your self-education in painting, going to museums, the incredible amount of visual work that you’ve made – collages, watercolors, and fans – and I was really excited to find out that you did a show at MoMA PS1 in 1980. It seemed as if you wrote the description of the show itself. You said something like, “It’s said there’s a relationship between her visual work and her poems. There is.” [Alice laughs] Which made me think it was absolutely written by you. I wonder about all of the work you’ve done making these objects.

Alice: I’m making them right now. I’m actually sitting talking to you at a table surrounded by the ones I’m in process with right now. I never stop making them but sometimes there are lapses because I haven’t finished one. But I’m always doing it. But I’ve interrupted your question.

Nick: I’m not sure there’s a question other than to let you talk about it.

Alice: My relationship to art. I’ve been very close friends with some artists, that started at the beginning as soon as I met Ted, then I met his friends. I got tremendously interested in the works that Joe Brainard and George Schneeman were doing. All of that whole art world opened up to me. But I had been interested in painting when I was in high school in Needles. I didn’t paint but I studied art history in a way. My mother ordered from the outside world a monthly book, like a set of lectures by John Canaday, that would come with these illustrations and prints and then I would look at them and read the description and try to figure out what he was talking and why he was talking about ti this way and I got very interested. When I met Ted everybody cut and pasted so I instantly started doing it and I never stopped. He and I would do it together. He would do it his way off in his corner and I would do it over in my corner. The way he did it was different from the way anyone else did it, and George Schneeman was totally fascinated by the way Ted worked with him when they collaborated. But I didn’t want to collaborate. I only wanted to collaborate with myself and that was my evil secret and it’s always been my evil secret that I that don’t want to do anything with anybody else. But I was so interested in George’s process and everybody said that he wouldn’t talk about his art. So I determined to make him talk about his art and went to see him all the time for that interview that’s also in Brilliant Corners.

Nick: And in Waltzing Matilda.

Alice: I went to ask him questions day after day and he became addicted to having me ask him questions, that was why he was willing to talk to me finally, I mean he just loved it. Then I wrote the essay kind of off-hand. Edwin [Denby] had really, really liked all of that, too. They really loved it that I had made George talk. You know, I was interested in all the people I refer to in the Art Institute essay, all of that, all those works. I was really torn up by postpartum depression and all that really healed and strengthened me, going out to the Art Institute and looking at the paintings then writing off them. All of the essays from that time are written out of a slight hysteria. They’re all written out of this desperation I felt at being depressed in that particular way. And I was always trying to declare myself well through the process of looking at this art and reading these books and writing these things, and I don’t know if that makes sense, but at a certain point I was healed. I was healed. I didn’t write those anymore and I didn’t have that tone anymore. I lost that particular tone but I was glad to because I felt better.

***

Alice: Poets have their own way of being critical and scholarly but it’s not the way you’re taught. And it can’t be systematized. For poets, it comes largely out of talking to each other, I think, and a lot of it happens when you’re young. You figure things out with your peers in late night drunken conversations and those are really important.

***

Nick: I wonder what it would look like to collect all of your works together. It would be this 2000-page collected poems. It’d be a suitcase-size book.

Alice: It’d be like a nineteenth century person, like Hugo or Charles Dickens or somebody.