scholarship & Books

From left to right: Dick Gallup, Joe Brainard, Ted Berrigan, Pat Padgett, Ron Padgett, c. 1963. Courtesy of the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library at Emory University.

My scholarship explores post-WWII American poetry with a focus small press publishing, little magazines, print culture, and literary institutions. Like my teaching with undergraduate students, this scholarship is multimodal—including a digital publishing project, book-length editorial projects, essays, book chapters, bibliography, interviews, presentations, and podcasts—and relies on primary source archival research as well as direct engagement with the writers I study. Excerpts from recent scholarship are included below. This work has been supported by a BSA-St. Louis Mercantile Library Fellowship from the Bibliographical Society of America, fellowships to the New York Public Library and the Raymond Danowski Poetry Library in Emory University's Rose Library, and a Strochlitz Travel Grant to the University of Connecticut. My past archival work also includes research at Stanford University, the University of California at San Diego, and the University of Essex.

My first book project, Publishing the New York School: Small Press Communities and American Poetry, explores the New York School as a series of writing and publishing communities from 1960-1990 grounded in a study of little magazines, small press networks, and alternative literary institutions. Under contract with Columbia UP.

I’m also in the research stage on another book-length project, The Poetry Business, that examines the role of the state, nonprofits, universities and philanthropy in the professionalization of American poetry.

Forthcoming projects include a chapter in Frank O’Hara in Context (Cambridge University Press); editing The Collected Poems of Jim Brodey (Nightboat Books); and a chapter in The Bloomsbury Handbook of Literary Editing.

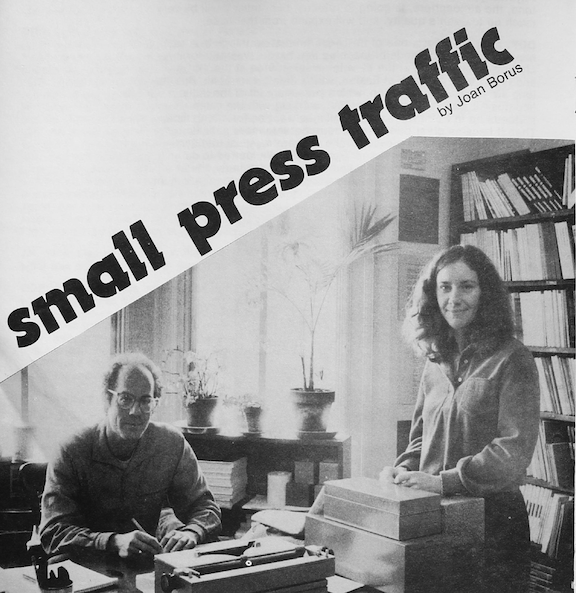

Photograph by Perci Chester of Robert Gluck and Denise Kastan in SPT. Cover of Intersection newsletter vol. 10 issue 2 (Summer 1980).

ESSAY: "Sustained beyond these Institutions: The Small Press Traffic Print Collection Archives”

A commissioned essay for Small Press Traffic, the San Francisco-based literary nonprofit organization, that serves as an introduction to the organization’s new digital archival project.

Since its establishment in 1974 as a few shelves of books sold on consignment in Paperback Traffic, the first commercial gay bookstore in the Castro, Small Press Traffic has facilitated decades of literary community, friendship, and arts organizing through its commitment to small press publishing. Driven by the scrappy ethos of alternative publishing, founders Denise Kastan and Jim Mitchell quickly transformed the consignment concept into its own nonprofit bookstore combining retail, readings, workshops, and distribution. The uniquely hybrid project joined a thriving local small press ecosystem encompassing such organizations as the West Coast Print Center, Small Press Distribution, the Before Columbus Foundation, New Langton Arts, and Intersection for the Arts. Ongoing transformations within the Bay Area’s literary communities, including lineages of San Francisco Renaissance and Beat writers intersecting with Language poetry, California Chicanx literature, and new forms of liberatory politics, were amplified by Small Press Traffic’s dynamic programming. “[T]here are generations of people that have come out of Small Press Traffic, the workshops, all of it,” said Robert Glück, who began the organization’s reading series in 1978. It was a space where “people formed relationships that lasted forever.”

REMEMBRANCES OF ALICE NOTLEY: “‘Always Being Myself’: Remembering Alice Notley” at The Poetry Foundation (August 2025); “A Splash Alive Forever” at The Poetry Project Newsletter no. 281 (Summer 2025); & PODCAST: Close Readings episode 49—Nick Sturm on Alice Notley ("At Night the States")

Alice survived in and because of poetry. That, and love.

She also thought a lot about time, timeliness, and timelessness, which have to do with different ways of considering poetry’s forms, but she refused linearity, which did not reflect her experience of art and of life. Because of this, her poetry carries the capacity to be instructive about, and to participate with, death and the dead. She wrote books with titles like When I Was Alive, Alma, or The Dead Women, and Grave of Light. At a conference on her work a few years ago she asked, “What can we learn from the fact that we don’t die?” She was suggesting that death is the state of becoming the substance of communication—that therefore we continue to have a form but not matter—and what does this mean? At the same gathering she tossed off the incredible statement, “Sometimes I think my entire oeuvre is a response to As I Lay Dying.” She was funny like that. Her inscription in my copy of When I Was Alive is simply: “to Nick, when I was alive.” (So close to “when I was Alice.”) She was funny, also, like that.

On the title page of When I Was Alive there is a small image of a black galleon ship. When I asked her about the ship imagery laced across her poetry and collages, she looked into me and recited this D. H. Lawrence couplet: “Have you built your ship of death, O have you? / O build your ship of death, for you will need it.”

Alice built her ship of death. It was everything she did.

EDITED BOOK: Conversations with New York School Poets edited by Rona Cran and Yasmine Shamma with contributions by Nick Sturm, Edinburgh University Press (2025)

Conversations with New York School Poets provocatively explores the question of what (and who) constitutes the New York School. The book features conversations with a wide range of poets, each speaking in captivating ways about where and how the New York School lives. It traces the stories of the poets’ journeys through New York, through poetry, and through friendships with one another. It contains plenty of gossip, alongside plenty of what poet Ron Padgett calls the “nuts and bolts” of poetic writing. Extensive in scope and coverage, Conversations with New York School Poets is an invaluable archive of modern and contemporary writing cultures in New York City and beyond.

Conversations: Alice Notley, Ron Padgett, Bernadette Mayer, Anne Waldman, Eileen Myles, Lewis Warsh, Edmund Berrigan, Anselm Berrigan, John Godfrey, Bob Rosenthal, Clark Coolidge, Tony Towle, Charles North, Ed Friedman, Maureen Owen, Jordan Davis, Elinor Nauen, Kimberly Lyons, David Shapiro, Vincent Katz, Patricia Spears Jones, Harris Schiff, Greg Masters, Lee Ann Brown, and John Yau.

EDITORIAL PROJECT: dossier of the poet Jim Brodey’s prose writings, “Jim Brodey, Electrified Prose” in Paideuma: Modern and Contemporary Poetry and Poetics Vol. 49 (August 2024)

from “The Human Shredder: An Introduction”:

The prose that Brodey pounded out along with his shimmeringly bent poems is the subject of this dossier for Paideuma. I am tempted to push us closer to the contents of this prose selection by offering up a buffet of even more mesmerizing biographical details that emerge from his prose—like how it was a handwritten note from Patti Smith in Brodey’s mailbox at the Chelsea Hotel that notified him of his friend Duane Allman’s fatal motorcycle accident, or when at the Electric Circus he gave a set of his poems to John Coltrane, or Brodey’s description of listening to Bob Dylan’s newly released Blonde on Blonde with Frank O’Hara only weeks before O’Hara’s untimely death. As these details suggest, Brodey was vibrantly enmeshed in the cultural fabric where music and poetry overlapped, skimming across a pantheon of musical innovators, fabled sites and encounters, and friendships with iconic artists. Figures as various as Louise Bogan and Eve Babitz, Robert Creeley and Robbie Robertson, populate his prose. Combined with his associations among underground comix artists and alternative publishing networks, as well as his forays into the film and sex industries, all of which readers will find out more about from this selection, these details show Brodey to be a charismatic hinge between some of the wildest corners of the American counterculture.

BOOK REVIEW: On The Miraculous Season: Selected Poems by V. R. “Bunny” Lang, ed. Rosa Campbell in The Poetry Project Newsletter no. 277 (Summer 2024)

The Miraculous Season, published early this year by the UK-based Carcanet Press, delivers this renewed edition of Lang’s poetry, building positively on the two collections of Lang’s writing that were assembled posthumously—The Pitch, privately printed in 1962, and V. R. Lang: Poems & Plays, published by Random House in 1975. Though these books brought Lang’s work into circulation for the first time beyond her publication in little magazines, both editions include the same forty-eight poems, an editorial choice that suggests a limited and definitive selection. As Lurie writes in her memoir of Lang, which acts as the introduction to the Random House edition, “Everything she wrote contained wonderful lines and fragments; almost nothing was complete.” Lang was brilliant, we’re told, but didn’t finish much. The implication is that what was deemed complete following Lang’s death—a process undertaken by her husband Bradley Phillips, whom she married at the end of her life, along with friends of Lang’s and input from O’Hara—is wholly accounted for in the available books. However, there are moments in Lurie’s memoir that tease a more capacious archive. Working to assemble a manuscript after her diagnosis with cancer, Lurie describes a frantic scene in which “beds and the floor were covered with Bunny’s poetry for years past, all typed on tissue sheets of onion skin paper.” The image of Lang surrounded by typescripts makes one wonder what other versions of her work might exist.

BOOK CHAPTER: “‘Our first literature’: The Poetics Underground of Joe Brainard’s New York School Comics” in Comics and Modernism: History, Form, Culture edited by Jonathan Najarian. University Press of Mississippi (2024)

It is not a coincidence that C Comics emerged within the New York School, a constellation of artists who had a deep appreciation for the aesthetics of popular forms like comics. Many New York School poets grew up in the so-called “Golden Age” of comic books and absorbed those visual and textual influences into their wide-ranging and eclectic extra-literary interests. The poet Bill Berkson, who frequently collaborated with Brainard on comics, describes their presence as organic and originary: “Comics were very natural. We had a feeling for how they worked. They were our first art and, in many respects, our first literature.” This familiarity with comics’ formal qualities and recognition of their interdisciplinary aesthetic value is on display throughout both issues of C Comics in the ways that Brainard and his collaborators subvert the standard principles of comics’ form and content. As a 1969 article in the alternative newspaper Kaleidoscope Chicago describes: “‘C’ comics were as heavy and as ‘far out’ (in a different way) as what gets published today (Joe Brainard did all the drawings and New York poets finished the texts), this up to 4–5 years ago, when there weren’t no ‘underground’ comix happening yet.” Attending to how New York School poets and artists experimented with comics not only offers a renewed prehistory of the comix underground; it also helps us to see how New York School comics constitute their own sub-genre of alternative comics.

EDITED COLLECTION OF ESSAYS: Post45 Contemporaries cluster on Little Magazines (June 2023)

Featuring contributions from a dozen early career scholars, poets, and librarians about post-1960 little magazines as key sources for new approaches to research and teaching.

from editor Nick Sturm’s introduction, “Deep Immersion in the Little Mags”:

This cluster emerged from two broad, reciprocal realizations about the study of little magazines: that post-1945 literary studies and periodical studies are largely not in dialogue, and that periodical studies as such is dominated by modern/modernist periodical studies. To put it another way, contemporary literary scholarship has been slow to absorb the basic precept of periodical studies as a subdiscipline, that periodicals like little magazines can and should be studied as a primary subject rather than as simply one type of evidence. Additionally, if we're going to urge the field forward, it's crucial to acknowledge that periodical studies has been mostly the study of periodicals and periodical print cultures, literary or otherwise, from the late nineteenth to the mid-twentieth-century. What this means is that the rapid expansion of periodical forms in the 1960s associated with avant-garde writing communities, the New Left, and underground newspapers — to list only a few examples — has not been the subject of sustained research either within the field of literary studies generally or periodical studies specifically.

ESSAY: “‘Chicago comes to be its own source’: Little Magazines and Chicago’s New York School Print Culture,” Chicago Review Vol. 60 No. 3/4—Special Feature: Small Press Poetry in the United States (September 2023)

By the end of the decade, inspired largely by Notley and Berrigan, more than a dozen young poets from Chicago had moved to New York to join the community around The Poetry Project at St. Mark’ s Church in-the-Bowery, a dense Midwestern migration lovingly described as “the Chicago Invasion” by Bob Holman, who had himself moved from Chicago to New York in 1973. While Ashbery eschewed the New York School as a label, Berrigan, who was well versed in the term’s aesthetic history, including its origins as a “complicated double joke,” embraced it. He is famous for jokingly recruiting young poets to New York School–style poetics, claiming “I used to tell people they could join [the New York School] for five dollars.” While this humorous sense of low-stakes permission accurately describes Berrigan’s model for how to disavow aesthetic gatekeeping in favor of more raucous and inclusive communities, studying his direct interventions in the lives of his students—particularly through the small presses and little magazines he encouraged those poets to edit—offers a more vivid portrait of Berrigan’s perpetuation of the New York School through its corresponding print cultures.

ESSAY: “Scrap Irons of Painful Mercy,” an essay-review of Selected Poems of Calvin C. Hernton at The Poetry Foundation (October 2023)

As he began participating in the coffeehouse readings on the Lower East Side and publishing in little magazines, Hernton’s desire to “make my stand / As a human being, / As a Black man” (“Emigrant”) brought him into a burgeoning community of Black writers and artists. In 1962, alongside poets Lorenzo Thomas, David Henderson, Ishmael Reed, and Askia Touré, among others, Hernton founded the Society of Umbra, a group whose workshops, public readings, and self-titled magazine became “the cradle of the Black Arts movement in New York,” as Amiri Baraka acknowledged. What brought Umbra together, Hernton wrote, was the need to “do something about the isolation and anonymity we felt.” Umbra became what Hernton called a “black arts poetry machine,” a collective that, though it lasted just two years, “constituted a lifetime.” Reed admits, “If The New Yorker calls me ‘fearless,’ it’s because, like Calvin Hernton, I had been a member of Umbra.” […] Hernton’s peers in Umbra recognized him as a visionary within the group. Joe Johnson wrote, “we heard Hernton singing what we were talking about.”

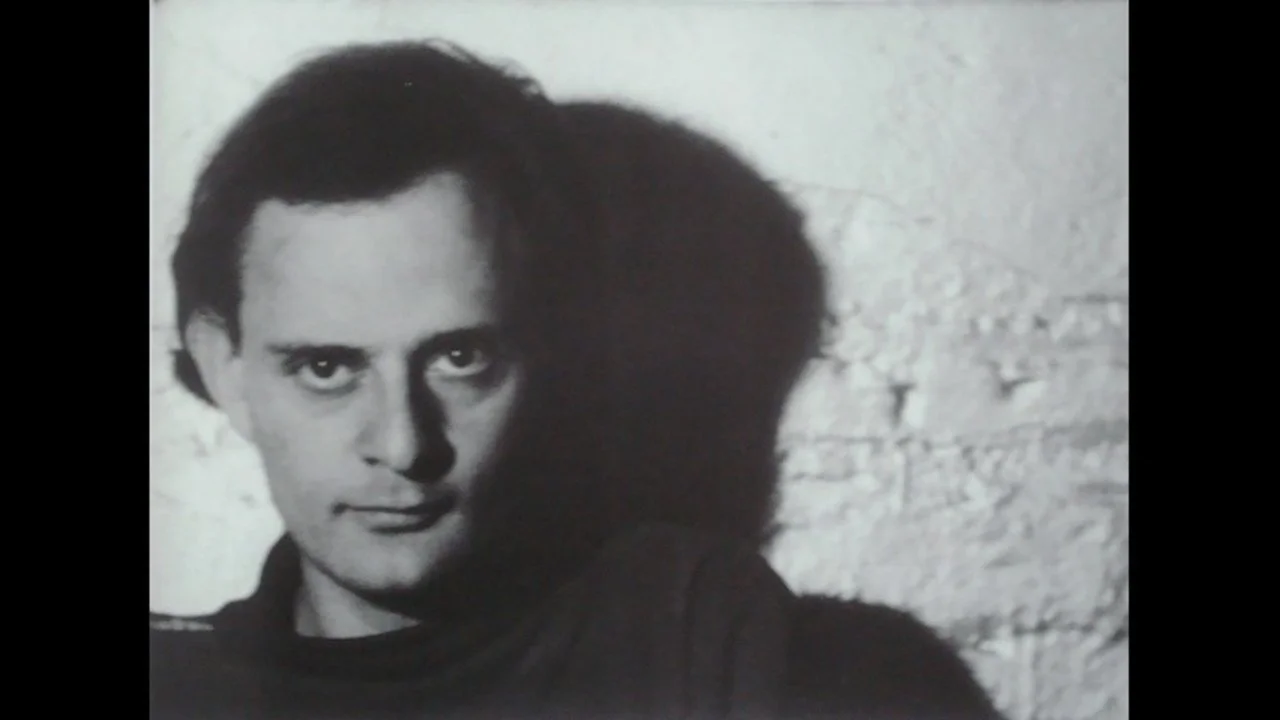

ESSAY: “Stronger Magic,” an essay on the life and work of poet Harry Fainlight at The Poetry Foundation (June 2023)

For a few brief years in the 1960s, Harry Fainlight was a shadowy prince of the New York underground. Though he published only one book in his lifetime—Sussicran (1965), narcissus spelled backward—his poetry is an incredible record of queer desire and visionary aesthetics formed through a unique mix of avant-garde and lyric sensibilities. “GOD IS PHOTOGRAPHING ME UPSIDE DOWN,” he writes in “Mescaline Notes,” indicating a focus on the visual and mystical that runs throughout his work. This poetic aperture developed in the experimental crucible of New York City in the early 1960s, situating him in a literary and sexual milieu packed with readings at Café Le Metro, avant-garde films by Andy Warhol, and cruising Times Square. When Fainlight died in 1982, Allen Ginsberg memorialized him as once “the most promising new consciousness poet in [the] English tongue.”

EDITED BOOK: Early Works by Alice Notley, edited and with an introduction by Nick Sturm (Fonograf Editions, February 2023)

Early Works collects Alice Notley’s first four out of print poetry collections, along with 80 pages of previously uncollected material. A must have for any Notley fan. Includes original collection cover artwork by Philip Guston, Philip Whalen, and George Schneeman, among others.

From editor Nick Sturm’s “Introduction” to Early Works:

In the author’s note that begins Grave of Light: New and Selected Poems 1970-2005, Alice Notley writes, “My publishing history is awkward and untidy, though colorful and even beautiful.” I have always been enamored of this sentence, which reminds us that an array of dispersed and varying publishing contexts are the original sites that give shape to such a book’s form. It is also something of an invitation into that color and untidiness, a prompt to become more curious about the awkwardness and beauty of Notley’s publishing history. This book, Early Works, accounts for a significant portion of that history by bringing back into print the complete versions of her first four books, a little-known 22-poem sonnet sequence, and a large selection of early uncollected poems gathered from little magazines. In doing so, Early Works joins an important set of recent volumes that put Notley’s earlier poetry back into circulation, including Manhattan Luck (Hearts Desire, 2014), which collects four long poems written between 1978 and 1984, and Songs for the Unborn Second Baby, originally published by United Artists in 1979 and reissued in a facsimile edition by London-based Distance No Object in 2021. Each in their own way, and especially taken together, these books continue to confirm that, as Ted Berrigan writes in The Poetry Project Newsletter in 1981, “Alice Notley is even better than anyone has yet said she is.”

My most recent interview with Notley, “Destined to tear this building down,” appears in The Poetry Project Newsletter (no. 273, September 2023)

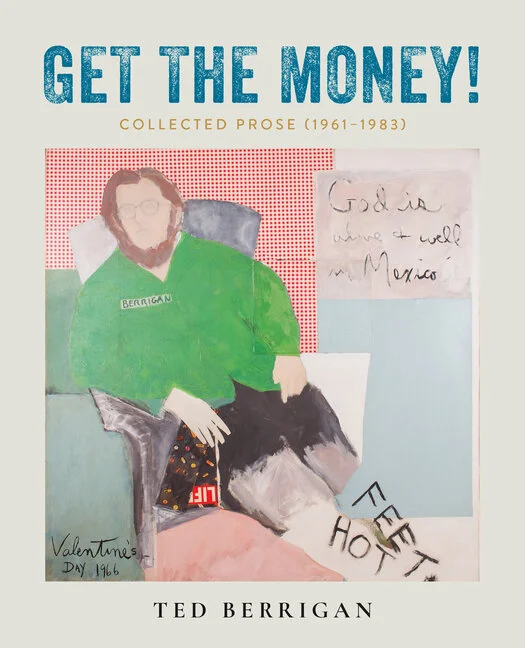

EDITED BOOK: Get the Money!: Collected Prose, 1961-1983 by Ted Berrigan, co-edited by Alice Notley, Anselm Berrigan, Edmund Berrigan, and Nick Sturm (City Lights Publishers, September 2022).

A monumental event in American poetry, Get the Money! brings together the essential prose writings of iconic New York School poet Ted Berrigan.

from Alicia Wright’s review in The Poetry Project Newsletter No. 270: “Get the Money! joins two other collections of Berrigan’s work: Nice To See You: An Homage to Ted Berrigan, edited by Anne Waldman (1991), a commemorative volume in which some of these prose works previously appeared, and The Selected Poems of Ted Berrigan (2011), edited by Alice Notley and Anselm and Edmund Berrigan. Get the Money! shows how Ted Berrigan worked in a range of different written modes, often paid and public, but just as consistently playful and private, bringing his characteristic candor to any written endeavor. With Nick Sturm’s archival steering and editorial eye supplementing the family’s effort, there’s a sense of completion, care, and even relief palpable in this latest volume, closest in spirit to a literary commonplace book. This collection will be indispensable for Berrigan aficionados and newcomers to his work alike. Like the richest records left behind by writers, Get The Money! makes explicit Berrigan’s cultivation of himself as a presence, writer, person, and literary mind.”

Review by Patrick James Dunagan at Caesura Mag

Review by Alicia Wright at The Poetry Project Newsletter

LECTURE: “Researching After the Last Avant-Garde,” in conversation with Daniel Kane; NEH Poetics Fellow Rose Library Lecture (April 2021):

With this sense of the messy and the provisional in mind, we should take Berrigan’s proposal of a “real New York School,” which suggests an established or somehow “authentic” avant-garde, as part of what is “very funny” about his genealogy. When Berrigan started editing C in 1963, he clearly did not imagine the New York School—“these guys,” he says, referring to John Ashbery, Kenneth Koch, James Schuyler and Frank O’Hara—as a reified canonical group that he was contending to ascend toward. Nevertheless, this is how some scholars have portrayed the relationship between a first and second generation of New York School poets. These narratives are often to the disadvantage of second-generation poets like Berrigan and Padgett whose work is cast as a symptom of a natural decline in originality and value from one group to the next, a kind of progressive watering down of first-generation potency. When David Lehman writes of the second generation that “all too often their poems are so derivative as to appear virtually indistinguishable,” or when Marjorie Perloff describes them as “the growing cult of Frank O’Hara,” a diverse community of writers is reduced to a homogenous set of acolytes. Berrigan often serves as the individual target of such incriminations, as when he is cast in a walk-on role in Perloff’s study of O’Hara: “when Ted Berrigan, one of O’Hara’s most ardent disciples, first arrived in New York fresh from the Midwest, he would stand patiently on Avenue A near their apartment, hoping to catch a glimpse of his idol.” One might argue this fawning scene is relatively innocuous, though when Perloff continues by describing Berrigan’s poems as “imitations” that “capture the O’Hara manner without the substance,” it is clear she is deploying a caricature of a star-struck Berrigan to prop up her narrative of O’Hara’s original genius. In these cases, labeling a poet as part of the Second-Generation New York School signals that we should read them as of secondary importance, if at all.

ESSAY: “Magic, Friends, Loyalty, Revolution,” an essay-review of Anne Waldman’s Bard, Kinetic at The Poetry Foundation (January 2023)

Waldman is now in her late 70s, and her kinetic exuberance is also tinged with elegy. An essay about her involvement with Occupy Art unfolds into a list of the artists and poets who died over the last decade—Baraka, Warsh, and John Giorno, among others—a reminder that her “alloys of artwork and political intervention” are bound up in the “human dimension” of lives, loves, and losses. The deaths of women contemporaries such as di Prima, Akilah Oliver, Bernadette Mayer, Bobbie Louise Hawkins, Joanne Kyger, and Etel Adnan are poignantly marked in Bard, Kinetic. “What she attempts to do in language,” she writes about Adnan, who died in 2021, “is a crisis upon an altar, a crise of the vocal vibrating heart.” In her introduction to a selection of correspondence between herself and Kyger, Waldman writes that the Bolinas-based poet, who died in 2017, “had an open screen in her being” and that her poems “had perfect balance.” “It took Gary Snyder and Allen [Ginsberg] too long to see what a great poet Joanne Kyger is!” she writes elsewhere in the book, reminding readers that she and her peers’ achievements were made within and against a patriarchal literary culture that regularly diminished those achievements. “In many instances,” Waldman writes in the section “Feminafesto,” “when all these alternative cultures and communities and lineages and affinities were coalescing and trembling and forming and reforming, I was often the only woman in the room.” Bard, Kinetic is a recovery project that shows these women working in the room alongside Waldman to reimagine that poetic culture.

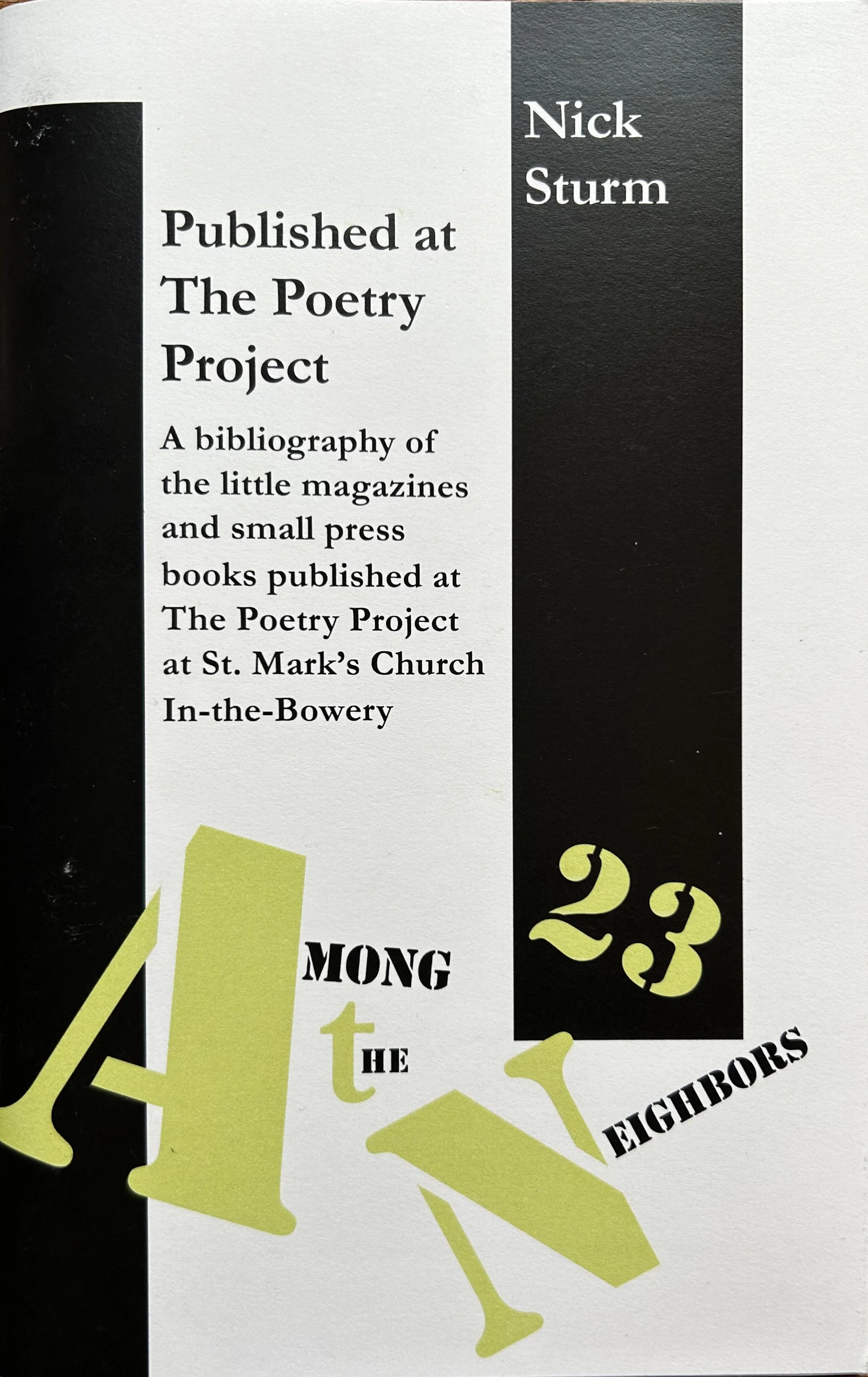

BIBLIOGRAPHY: Published at The Poetry Project: A bibliography of the little magazines and small press books published at The Poetry Project at St. Mark’s Church In-the-Bowery, “Among the Neighbors” bibliographic pamphlet series, No. 23 (November 2022)

from the introduction “The Mimeo Poetry Kingdom of New York”:

Studying mimeographed books and periodicals from the 1960s to the 1980s, one quickly becomes familiar with a common refrain on the colophon of these publications, as in Ted Berrigan’s A Feeling for Leaving: “Published at The Poetry Project, St. Mark’s Church In-The-Bowery, New York.” In addition to recognizing The Poetry Project as an experimental epicenter for readings, performances, and work-shops, the pervasiveness of these notes reminds us that the Project is also one of the main sites of post-war alternative publishing. In fact, The Poetry Project’s electric nine-hole Gestetner duplication ma-chine, purchased by the then-new arts institution in 1966, facilitated one of the largest surges of mimeographed literature in the 20th century. Hundreds of issues of little magazines and tens of thousands of copies of small press books were published at St. Mark’s Church thanks to its open-door policy as a full-service underground publishing center.

Email “Among the Neighbors” series editor Edric Mesmer (esmesmer@buffalo.edu) for copies and to be added to the AtN mailing list

Photograph of Eileen Myles by Tim Milk, 1983.

ESSAY: “‘I’ve never liked mimeo’: Eileen Myles, Little Magazines, and the ‘Umpteenth-Generation New York School,’” in special issue “Eileen Myles Now” of Women’s Studies (October 2022)

This essay seeks to describe Myles’s relationship to the New York School, including what it might mean to “leave it” as a queer poet, through a reading of their little magazine dodgems. By situating dodgems within a larger periodical network and describing Myles’s resistance to established traditions in the print culture of the New York School, particularly their rejection of mimeograph printing in favor of newer technologies like xerox, this essay argues that Myles’s little magazine is an important record of a material and aesthetic shift in New York School writing communities. As Seita argues, little magazines are the medium that “capture and create provisional and heterogenous communities” (2). Looking to a magazine like dodgems offers a way of tracing Myles’s role as a poet-editor and publisher within those provisional communities that does not rely on categorizing them within an amorphous “umpteenth-generation New York School.” Unlike generational formations, descriptions of avant-garde writing communities that emerge from the study of little magazines have the potential to charge labels like New York School with a surprising elasticity. As a queer poet, Myles’s version of the New York School “summons a different, more anarchic roster—one that might also accommodate Cooper, Kathy Acker, Tim Dlugos, David Trinidad, and David Wojnarowicz, among others” (Nelson 171).

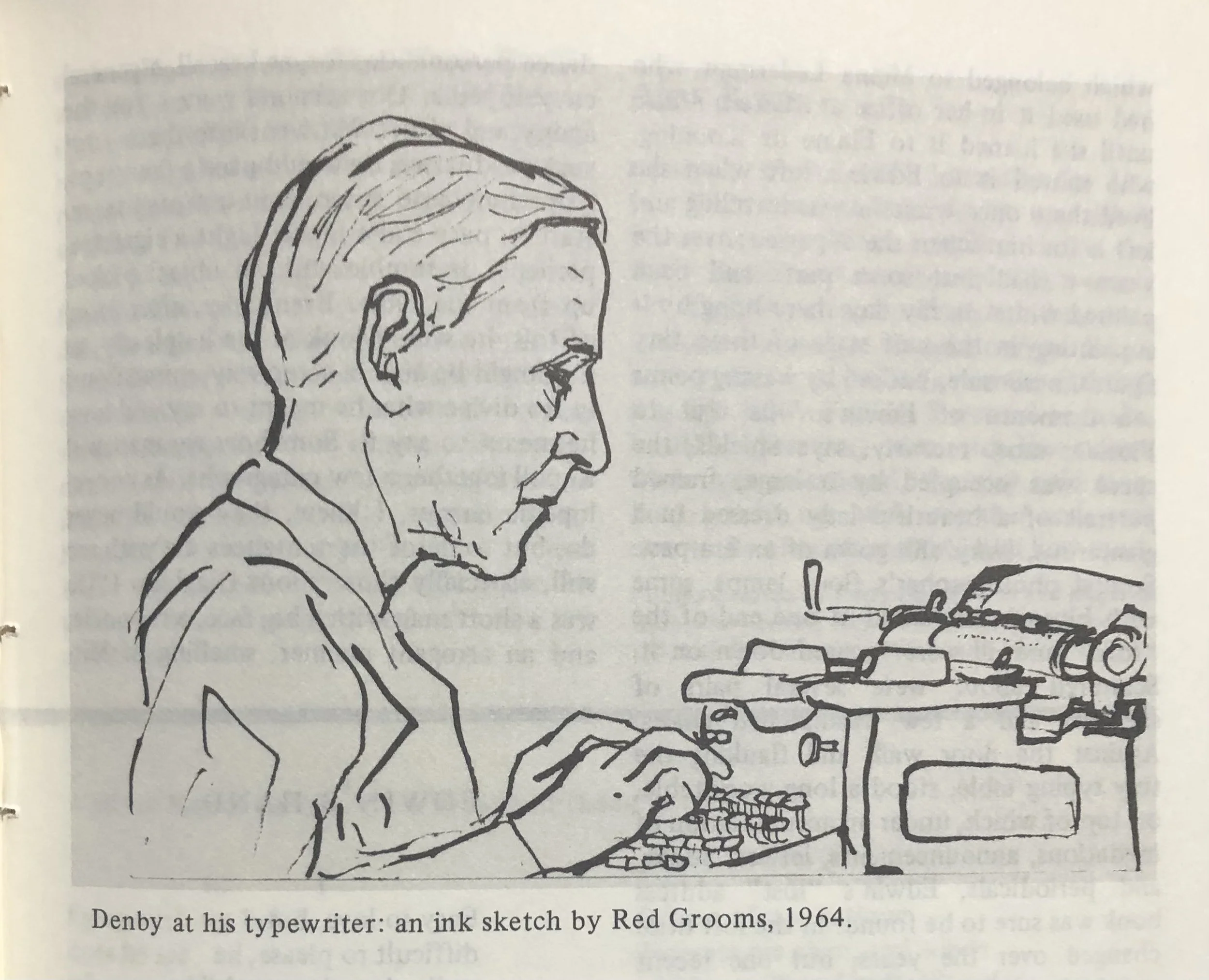

ESSAY: “Feelings Are Our Facts,” an essay on the life and work of poet and dance critic Edwin Denby at The Poetry Foundation (September 2022)

As O’Hara wrote, Denby’s crystalline intellect had a way of illuminating “[t]he ballet, the theatre, painting and poetry, our life accidentally in co-existence,” offering “an equation in which attention equals Life, or is its only evidence.” When Denby died in 1983, three consecutive evenings of tributes at St. Mark’s Church in-the-Bowery and Lincoln Center brought together “as magnificent a mix of the art and dance worlds as ever gathered in New York,” the Ballet Review noted. John Ashbery celebrated Denby as “American poetry’s best-kept secret.” Arlene Croce, who founded Ballet Review “under the sign of Denby,” called his Looking at the Dance (1949) “the most universally admired book of dance criticism in American publishing history.” Speaking to Denby’s generative aura, artist Mimi Gross described how he “shared that mystic sense, the religion of art, and without ever saying it in words could plant it in another person to grow.” The image of “Saint Edwin,” as critic David Vaughan described him in 1965, was even endorsed by the city of New York. A representative of then-Mayor Ed Koch appeared at Denby’s memorial “to say officially as well as personally that New York City recognizes Edwin Denby and feels his loss and joins in remembering and appreciating him.” Denby was “part of the intellectual history of New York,” as Croce wrote, nearly coincident with the city itself. From his loft at 145 W. 21st Street in Chelsea, where he lived for nearly 50 years, Denby intimately accompanied the shaping of 20th-century art.

From “Edwin Denby Remembered—Part II” in Ballet Review Vol. 12 No. 2 (Summer 1984)

ESSAY: “‘Wivenhoe is enrolling en masse’: Notes on the New York School in the UK” at The Stinging Fly (May 2022)

‘Pity we’ve got this damn ocean between us,’ writes Lee Harwood to Ted Berrigan in March 1965. Harwood was offering a set of Tristan Tzara translations for Berrigan to publish in his little magazine C: A Journal of Poetry. ‘It’d be much easier if you could just leaf through & pick-out what you wanted. Stupid pipe-dreams.’1 If a more material link between avantgarde communities of poets in the United States and Great Britain was a pipe dream in early 1965, Allen Ginsberg’s visit to the UK two months later, which precipitated the storied International Poetry Incarnation reading at Royal Albert Hall, transformed that dream into a reality. As Harwood describes to Berrigan in July, ‘about [the] England magpoemscene—since Allen Ginsberg arrived early May, a wierd [sic] poem fever has infected the whole country. Everything happening every day. And now he’s left, the fever still raging—thank god.’2 This fever instigated Harwood to publish his own little magazine Tzarad, the first issue of which included work by American poets John Ashbery and Gerard Malanga. The second issue of Tzarad, ‘a special New York issue,’ is an incredible document of New York School writing featuring work by Berrigan, Malanga, Joe Brainard, Kenward Elmslie, Barbara Guest, Dick Gallup, Bernadette Mayer, Peter Schjeldahl, Lewis Warsh, and Joseph Ceravolo. Despite the ocean between them, poets like Harwood and Berrigan were contributing to a robust transatlantic print culture that was introducing new American poetry, and especially the poetry of the New York School, to British audiences.

BOOK CHAPTER: “‘There are no typographical errors in this edition’: Burroughs’s Textual Infection of the New York School” in Burroughs Unbound: William Burroughs and the Performance of Writing edited by Stanley Gontarski. Bloomsbury Academic (November 2021)

Published in 1965 by Ted Berrigan’s “C” Press, Burroughs’ TIME, which includes four drawings by Gysin, is the most sustained textual-visual cut-up experiment that he produced in the 1960s…. Only the seven-page “The Dead Star,” published in a late issue of My Own Mag and reissued as a pamphlet in the Nova Broadcast series in 1969, is visually similar to TIME. Standing on its own, TIME is notable for its length, the variety of visual texts and cut-up styles it incorporates, and its weaponized intertextuality with Luce’s magazine. It is also notable as one of the most little-known of Burroughs’ works, released in an edition of 1,000 copies that are now available mostly in university special collections and as rouge PDFs. It remains nearly unaccounted for in scholarship. Despite the archival turn in literary scholarship and increased focus on critical recuperation projects, especially the genetic criticism of Burroughs’ novels, TIME has yet to be recognized as a critical hinge in mid-1960s avant-garde American aesthetics. A turn to TIME addresses this gap in scholarship of Burroughs’ work and allows for a closer look at the aesthetic production that coincided with his tumultuous, influential visit back to the United States from 1964 to 1965—a year where Burroughs swirled through New York City’s art scenes. To the younger poets of the so-called “Second Generation” New York School—poets such as Berrigan, Ron Padgett, Joe Brainard, and Tom Veitch—Burroughs arrived in New York City as a “returning hero” (Veitch 2009) who, through the publication of his Nova Trilogy novels and regular appearances in avant-garde magazines like Evergreen Review, had been the source of an array of innovative composition methods. Though glossed over or unacknowledged by scholars, there is a deep aesthetic reciprocity between Burroughs’ methods and the experimental compositions of the New York School writers who met and collaborated with Burroughs during this time. “The word is a virus” (1985: 51), Burroughs famously announces, though his textual infection of the New York School has gone undiagnosed.

ESSAY: “Differing freak wonder,” an essay on the life and work of poet Jim Brodey at The Poetry Foundation (February 2021)

A close friend of Frank O’Hara and Duane Allman, and present at both the Berkeley Poetry Conference and Monterey Pop Festival, the poet Jim Brodey is the unacknowledged legislator of the aesthetic vortex where the New American Poetry meets the electrified counterculture of the 1960s. John Godfrey has called Brodey “a voracious post-lysergic romantic,” an accurate measure of Brodey’s emergence from the scenes of sex, drugs, rock-and-roll, and poetics that nurtured his own “differing freak wonder,” as Brodey writes in Identikit (1967). While poets such as Patti Smith, Ed Sanders, Richard Hell, and Jim Carroll remade their careers by taking the stage as musicians, Brodey became the poet-rock critic of his generation…. The poems Brodey published in C: A Journal of Poetry, The World, and his own little magazine Clothesline amplified a surreal rock resonance…

ESSAY: “I make these collages and write”: Alice Notley’s Visual Art, at Jacket2 (December 2020)

Looking through Notley’s collages, collaged fans, watercolors, portraits, masks, assemblages, and book covers in the archive, it is astounding that some curator or gallery has not approached Notley about doing a retrospective. An edited volume of Notley’s visual art should follow, akin to recent books on Ashbery and Helen Adam’s collages. Intricate and mysterious, seeing her visual art exposes one to the incredible breadth of Notley’s life as a poet. It is meaningful that so much of her visual work dates from the 1970s and ʼ80s, the two decades when Notley’s first seventeen books were published, all of which are out of print and difficult to find. Perhaps such a retrospective would not only lead to greater interest in her visual art but also to a return to the early poetry that is yet to be widely read and celebrated. Fortunately, the Special Collections and Archives at UC San Diego recently released a digital collection of nearly one hundred of Notley’s artworks, providing public access to the largest array of Notley’s visual art since her 1980 PS1 show.

As she recently told me, “I’ve continued to do it over time in such a way that people want to look at the collages and talk about them now, right now, and as I write this letter to you…I realize that this was always going to happen and it is right.”

Cross, Alice Notley Papers, MSS 319, Special Collections and Archives, UC San Diego. Click to view a larger version of this image.

Willem de Kooning, Excavation, 1950

© 2018 The Willem de Kooning Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

ESSAY: “Unceasing Museums: Alice Notley’s ‘Modern Americans in Their Place at Chicago Art Institute,’” at ASAP/J—with Notley’s original essay republished here (March 2019)

As Notley wanders through the museum over the course of at least two days, she describes a partial renovation of the Art Institute in 1974 that moved portions of the twentieth-century American paintings to a new exhibition space. The renovations instigate a narrative for Notley; the almost magical reordering of these paintings provides a new way for the poet to understand the fluid, contingent arrangements in her writing process. While Notley catalogues the intimate reciprocity she has built with dozens of paintings, much of the essay finds her attention yoked to Excavation, de Kooning’s “midcentury masterpiece,” a painting acquired in 1952 after its showing in the Art Institute’s 60th Annual American Exhibit. Following its acquisition, De Kooning’s Excavation was villainized by Chicago anti-modernists for being a “monstrous” painting. “We doubt,” one critic speculated, “whether there are many Chicagoans who would like to see more and bigger de Koonings and his ilk hanging in the permanent collection.”

Cover of Gare du Nord Vol. 2 No 2. published in 1999 by Alice Notley & Douglas Oliver, Paris.

DIGITAL SCHOLARSHIP PROJECT: Alice Notley’s Magazines

This digital publishing project makes available fully searchable facsimile PDF editions of the three different magazines edited by poet Alice Notley. This includes the complete runs of Scarlet (1990-1991) and Gare du Nord (1997-1999), both co-edited with Douglas Oliver, and CHICAGO, a legal-size mimeograph magazine published from 1972-1974 in Chicago and Wivenhoe in Essex, England. Click through to the project page to read the issues, see complete tables of contents, and read the essay “‘Guided by Right Spirit’: The Radical Editorial Vision of Alice Notley and Douglas Oliver in Scarlet and Gare du Nord.” Bookending a decade of incredible work and new life, Scarlet and Gare du Nord are vital records of the collaborative refusal and care that Notley and Oliver produced together as they moved between New York City and Paris. Scarlet, published in five issues from 1990-1991, seeks to establish a poetry newspaper that is "guided by right spirit," a tacit reference to the political party "Spirit" founded by Will Penniless and friends in Penniless Politics, and tracks the shifting literary and political landscapes concurrent with the First Gulf War and the ongoing AIDS crisis. The magazine's run concluded in March 1992 with the publication of The Scarlet Cabinet, a compendium of books by Notley and Oliver, including the first complete publications of The Descent of Alette and Penniless Politics, both of which were serialized in the magazine. The end of Scarlet also marks the end of Notley's life in New York City in the iconic apartment at 101 St. Marks Place. Five years later in Paris, Notley and Oliver began publishing Gare du Nord, a magazine "to act as a rail crossing-point" between glossy poetry magazines and the emergence of online poetry websites, and more widely, between cultures, between genders, and between genres. The five issues of Gare du Nord span from 1997-1999. The "right spirit" of Scarlet, what they describe as "work which unities vision to concern," extends to Gare du Nord in Notley's and Oliver's commitment to a radical editorial vision that values magazine publishing as an extension of those intimacies, truths, and questions which are the subject of one's life, not a personal marketing strategy or poetic allegiance.

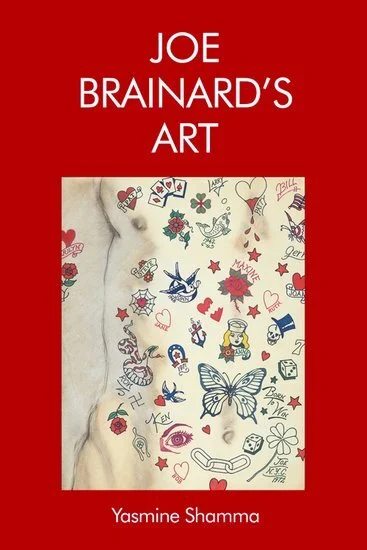

BOOK CHAPTER: “'Fuck work': The Reciprocity of Labor and Pleasure in Joe Brainard's Writing," in Joe Brainard’s Art edited by Yasmine Shamma (Edinburgh University Press, 2019)

Cover of Joe Brainard’s Art edited by Yasmine Shamma, EUP (2019).

As Richard Deming shows, Brainard’s ambitious work ethic and his art’s ‘emphasis on labor, attention, and gratitude’ produces a devotional aura full of humor and free of Pop Art’s ironized repetitions. ‘Devotion is a practice, an activity,’ writes Deming, and rather than Andy Warhol’s machine-like coolness or his friend Ted Berrigan’s goofy sketches, ‘the devotion of [Brainard’s] art is to the act of devotion itself’.[i] Brainard’s 1975 Fischbach Gallery show, a comic, fanciful flood of 1,500 miniatures, is testament enough to his meticulousness. But devotional labor is often a simultaneous articulation of commitment and uncertainty, an act of attentive care that is also an anxiety-ridden self-flagellation. The latter quality is what Lee Wohlfert’s review of the Fischbach show in People describes as Brainard’s ‘rigorous logic,’ the seemingly endless transformation of ‘pack-rat clutter’ into his aesthetic ‘obsessions’.[ii] Brainard’s devotion is a description of the practice that opens up the time for such obsessions to emerge, be arranged, and materialize.

***

Both in his visual art and his writing, it is Brainard’s aesthetic sense of the glimmering underside of consumerism, not materialism or capitalistic labor as an end-in-itself, that motivates his aesthetic. The objects lining the store shelves—shampoo, soda bottles, clothing—like the objects that he would use in his intricate pop assemblages, attract Brainard’s attention for their aesthetic value—a color, a line, a texture—and not for their use value.

from Berrigan’s ARTnews article on Alice Neel, “The Portrait and Its Double,” Volume 64, Number 9, January 1966.

ESSAY: "'The Pollock Streets': Ted Berrigan's Art Writing" (Part 1 and Part 2) at Fanzine (January 2016)

Berrigan’s January 1966 article on Alice Neel, “The Portrait and its Double,” with its titular allusion to Antonin Artaud, serves partly as an opportunity to arrange and merge various influences. Neel’s two 1960 portraits of O’Hara, which are described in the essay, likely drew Berrigan to her work, whose “fiercely independent realist” style, as he describes it, had been suffering from a comparative lack of recognition under the heroic pressures of abstract painting. Here Berrigan is interested in describing the effects of Neel’s tendency to create two portraits of each individual she paints: the first more stable and recognizable, a casual portraiture; the second more allegorical and symbolic, a way of externalizing interior crisis. He describes her doubling as a process of necessary emotional echoing: “Each second portrait has resulted because Alice Neel has seen another person in her subject. Whether what she has seen makes ‘more’ or ‘less’ of the person, or ‘something else,’ both her vision and the new portrait assert the possibility of other results.” The possibility of other results, of repetition and transformation, is also what motivates Berrigan’s acts of doubling, such as when he appropriates the lines of other writers in order to generate new energies, or when the lines of The Sonnets continually reappear in an out-of-sync parade of echoes.

Sturm and Alice Notley, New York City, November 8, 2022.

INTERVIEW: "Seeing the Future: A Conversation with Alice Notley" at the Poetry Society of America (October 2017)—an interview on the occasion of Alice Notley: Live in Seattle, a vinyl-record recording of Notley performing released by Fonograf

Nick Sturm: What does it mean to be irreducible?

Alice Notley: Oh, well, everything is. That's the problem with the thing between a university and the people who are working in the field. The university's job is to be conservative, it's their job. They're supposed to say things and hold onto them and teach them and make sure that they're handed on from generation to generation. The poet's job is this entirely other thing. It's to respond to what's going on right now at the same time as knowing everything already that the university is teaching. It's a very hard job and you don't get paid for it. I've only recently come to see that the world doesn't think very highly of me. I always thought that I would get a great deal of respect for being a poet but then the world really does only respect people whose work is monetary. It's sort of like being a trainspotter or something. I think that's how they think of you, that you're being a trainspotter. I've always thought that it was the greatest thing anyone could be and I thought that everybody must know that it was the greatest thing that anyone could be, that that was what I was trying to do.

PODCAST: “Teaching the Archives,” episode 416 of Lost in the Stacks, a research library radio show on Georgia Tech student radio WREK (March 2019)

It’s not every day that I have the opportunity to hop on the radio to talk about teaching the archives, let alone to curate a set list of Ted Berrigan-centric New York School-related songs, but that’s exactly what Lost in the Stacks, the research library rock’n’roll radio show at Georgia Tech’s WREK asked me to do for our episode “Teaching the Archives.” It was so fun to be able to talk about the Raymond Danowski Poetry Library at Emory University and Berrigan’s poetry in such a vivid, energetic medium. Lost in the Stacks describes itself as “the original research-library rock'n'roll radio show! Broadcasting on WREK Atlanta, each show features an hour of music, interviews, and library talk united by a common theme.” It’s an incredible show with episodes about open access issues, citizen archiving, exciting original research, all things library culture, and refreshing perspectives on the work of libraries, archives, and the folks who make them run—plus great music.

Full list of published scholarship and reviews (2010-2022) with links and PDFs via Google Drive:

Published at The Poetry Project: A bibliography of the little magazines and small press books published at The Poetry Project at St. Mark’s Church In-the-Bowery, “Among the Neighbors” bibliographic pamphlet series, no. 23, University at Buffalo, Nov. 2022.

“‘I’ve never liked mimeo’: Eileen Myles, Little Magazines, and the ‘Umpteenth-Generation New York School,’” in special issue “Eileen Myles Now” of Women’s Studies, Oct. 2022: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00497878.2022.2130924

“Feelings Are Our Facts,” an essay on poet and dance critic Edwin Denby, The Poetry Foundation, Sept. 2022: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/articles/158659/feelings-are-our-facts

“‘Wivenhoe is enrolling en masse’: Notes on the New York School in the UK,” The Stinging Fly, May 2022: https://drive.google.com/file/d/110Y2Jgb6fwClTQ12NlHdsLOxQsOJvcw-/view

“‘There are no typographical errors in this edition’: Burroughs’s Textual Infection of the New York School,” in Burroughs Unbound: William Burroughs and the Performance of Writing edited by Stanley Gontarski. Bloomsbury Academic, Nov. 2021: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1p56YIXZJ97UNw4DQ34CZ-2kFleCXdZbn/view

“A Conversation with Maureen Owen and Nick Sturm,” Rose Library Presents: Community Conversations, a podcast series from Emory University’s Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, June 2021: https://open.spotify.com/episode/3Go6l2qXNdU3cnxtxvOdnK

“Differing Freak Wonder,” an essay on the life and work of poet Jim Brodey, The Poetry Foundation, Feb. 2021: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/articles/155332/differing-freak-wonder

“‘The beauty of this world knocked me off my feet’: The Poetry of Dick Gallup (1941–2021),” The Brooklyn Rail, February 2021: https://brooklynrail.org/2021/02/poetry/The-beauty-of-this-world-knocked-me-off-my-feet-The-Poetry-of-Dick-Gallup

“A Brief History of The Poetry Project Newsletter,” The Poetry Project Newsletter No. 263, Winter 2021: https://www.poetryproject.org/publications/newsletter/263/a-brief-history-of-the-poetry-project-newsletter

“The Fires Behind Him: Lorenzo Thomas’s Collected Poems records a lifelong commitment to the liberatory potential of Black nationalism,” The Poetry Foundation, December 16, 2019: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/articles/151701/the-fires-behind-him

“‘What Else Might Be Available’: Three Contemporary Lineages of the Poetry Project,” Georgia Review, November 25, 2019: https://www.thegeorgiareview.com/posts/what-else-might-be-available-three-contemporary-lineages-of-the-poetry-project-on-stacy-szymaszeks-a-year-from-today-simone-whites-dear-angel-of-death-and-edmun/

“On Joanne Kyger’s chapbook Trip Out & Fall Back,” essay contribution to digital archive series “Chapbooks of the Mimeo Revolution” hosted by Poets House, September 24, 2019: https://digitalcollections.poetshouse.org/digital-collection/chapbook-collection/Trip-Out-%26-Fall-Back

“On James Schuyler’s chapbook The Fireproof Floors of Witley Court,” essay contribution to digital archive series “Chapbooks of the Mimeo Revolution” hosted by Poets House, July 24, 2019: https://digitalcollections.poetshouse.org/digital-collection/chapbook-collection/The-Fireproof-Floors-of-Witley-Court

“‘Fuck work’: The Reciprocity of Labor and Pleasure in Joe Brainard’s Writing,” in Joe Brainard’s Art, edited by Yasmine Shamma. Edinburgh University Press, April 20, 2019: https://global.oup.com/academic/product/joe-brainards-art-9781474436663?cc=us&lang=en& // https://drive.google.com/file/d/1kYTVh6QXHaC9Mk1kXMDCxfq5wlm_Oqf9/view

“Teaching the Archives” episode 416 of Lost in the Stacks, a research library radio show on Georgia Tech student radio WREK, March 15, 2019: http://lostinthestacks.libsyn.com/episode-416-teaching-the-archives?tdest_id=157087

“Unceasing Museums: Alice Notley’s ‘Modern Americans in Their Place at Chicago Art Institute,’” in ASAP/J with republished edition of Notley’s original essay, March 12, 2019: http://asapjournal.com/unceasing-museums-alice-notleys-modern-americans-in-their-place-at-chicago-art-institute-nick-sturm/ and http://asapjournal.com/modern-americans-in-their-place-at-chicago-art-institute-an-article/

“Life in Scatter: Bill Berkson’s memoir reveals a poet both of—and ahead of—his time,” The Poetry Foundation, Jan. 28, 2019: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/articles/149049/life-in-scatter

“‘Thinking with my hands’ in the archive: Second Generation New York School Gems,” Archives and Special Collections Blog, The University of Connecticut, Jan. 14, 2019: https://blogs.lib.uconn.edu/archives/2019/01/14/thinking-with-my-hands-in-the-archive-second-generation-new-york-school-gems/

Review of What is poetry? (Just kidding, I know you know): Interviews from The Poetry Project Newsletter (1983–2009) edited by Anselm Berrigan, Georgia Review, Spring 2018.

“Seeing the Future: A Conversation with Alice Notley,” Poetry Society of America, Oct. 25, 2017: https://poetrysociety.org/features/interviews/seeing-the-future-a-conversation-with-alice-notley

“From J to C: Jack Spicer’s and Ted Berrigan’s Shared Mimeograph Revolution,” Following the Fellows Series in connection with Emory University’s Rose Library Fellowship, August 23, 2016: https://scholarblogs.emory.edu/marbl/2016/08/24/ftf-nick-sturm/

“‘All this pain is necessary’: Amiri Baraka’s SOS: Poems 1961-2013,” ArtsATL, April 4, 2016: https://www.artsatl.org/review-all-pain-necessary-amiri-barakas-sos-poems-1961-2013/

“In the Garble: A Review of Alice Notley’s Negativity’s Kiss,” Fanzine, Feb. 18, 2016: http://thefanzine.com/in-the-garble-a-review-of-alice-notleys-negativitys-kiss/

“The Pollock Streets: Ted Berrigan’s Art Writing, Part I & II,” Fanzine, Dec. 12, 2015 and Jan. 18, 2016: http://thefanzine.com/the-pollock-streets-ted-berrigans-art-writing-part-i/ and http://thefanzine.com/the-pollock-streets-ted-berrigans-art-writing-part-ii/

Review of SOFT THREATS, Alexis Pope. On the Seawall: http://www.ronslate.com/thirteen-poets-recommend-new-recent-titles/

Review of GREAT GUNS, Farnoosh Fathi. On the Seawall: http://www.ronslate.com/fourteen-poets-recommend-new-and-recent-titles/

“Broken Umbrellas”: Authors on Artists Series. Bright Stupid Confetti: http://brightstupidconfetti.blogspot.com/2013/06/authors-on-artists-nick-sturm-on-broken.html

Review of NOTES FROM IRREVELANCE, Anselm Berrigan. Coldfront Magazine.

Review of BRIGHT BRAVE PHENOMENA, Amanda Nadelberg. On the Seawall: http://www.ronslate.com/eighteen-poets-recommend-new-recent-collections/

Review of LEAVING THE ATOCHA STATION, Ben Lerner. Puerto del Sol.

Review of NEW YEAR’S DAY, Genya Turovskaya. Coldfront Magazine.

Review of I WANT TO OPEN THE MOUTH GOD GAVE YOU BEAUTIFUL MUTANT, Bianca Stone. Read This Awesome Book: http://readthisawesomebook.blogspot.com/2012/04/i-want-to-open-mouth-god-gave-you.html

Review of OF LAMB, Matthea Harvey & Amy Jean Porter. Read This Awesome Book: http://readthisawesomebook.blogspot.com/2012/04/of-lamb-by-matthea-harvey-amy-jean.html

Review of OBJECTS FOR A FOG DEATH, Julie Doxsee. Whiskey Island. Republished online in The Volta: http://www.thevolta.org/fridayfeature-objectsforafogdeath.html

Review of EITHER WAY I'M CELEBRATING, Sommer Browning. Whiskey Island. Republished online in The Volta: http://www.thevolta.org/fridayfeature-eitherwayi'mcelebrating.html

Review of CALIFORNIA, Jennifer Denrow. Read This Awesome Book: http://readthisawesomebook.blogspot.com/2011/12/california-by-jennifer-denrow.html

Review of TOPOGRAPHIES DRAWN WITH A DIVINE CHAIN OF BIRDS, Tim Van Dyke. iO: A Journal of New American Poetry.

Review of THE DISINFORMATION PHASE, Chris Toll. Read This Awesome Book: http://readthisawesomebook.blogspot.com/2011/11/disinformation-phase-by-chris-toll.html

Review of chapbooks from Emily Pettit, James Gendron, Luke Bloomfield, Erika Jo Brown, and John Deming, H_NGM_N.

Review of MONEY SHOT, Rae Armantrout. The Laurel Review, Summer 2011. Republished online in The Volta: http://www.thevolta.org/fridayfeature-moneyshot.html

Review of THE NERVOUS FILAMENTS, David Dodd Lee. The Laurel Review, Summer 2011.

Review of FABLES, Sarah Goldstein. The Rumpus: https://therumpus.net/2011/07/fables/

Review of THE TREES THE TREES, Heather Christle. HTMLGIANT: http://htmlgiant.com/reviews/heather-christles-the-trees-the-trees/

Review of DESTROYER & PRESERVER, Matthew Rohrer. On the Seawall: http://www.ronslate.com/nineteen_poets_recommend_new_recent_titles

Review of LE SPLEEN DE POUGHKEEPSIE, Joshua Harmon. Barn Owl Review: http://www.barnowlreview.com/reviews/harmon.html

Review of I AM NOT A PIONEER, Adam Fell, On the Seawall: http://www.ronslate.com/twenty-poets-recommend-new-recent-titles/

Review JEREMY SCHMALL & THE CULT OF COMFORT, Jeremy Schmall. HTMLGIANT: http://htmlgiant.com/reviews/jeremy-schmalls-jeremy-schmall-the-cult-of-comfort/

Review of I HEART YOUR FATE, Anthony McCann. H_NGM_N.

Review of THE BIGGER WORLD, Noelle Kocot. Coldfront Magazine.

Review of THE GRIEF PERFORMANCE, Emily Kendal Frey. Barn Owl Review: http://www.barnowlreview.com/reviews/Frey.html

Review of COME ON ALL YOU GHOSTS, Matthew Zapruder. Barn Owl Review: http://www.barnowlreview.com/reviews/zapruder.html

Select conference presentations and lectures on the New York School:

“Fifty Years of The Poetry Project Newsletter,” moderated conversation with current and past editors of The Poetry Project Newsletter, The Poetry Project at St. Mark’s Church; Dec. 2022

“Celebrating Get the Money! Collected Prose, 1961-1983 by Ted Berrigan,” moderated conversation with co-editors of Berrigan’s collected prose in collaboration with Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Columbia University; Nov. 2022.

“The Bibliographic Underground: How ‘Evil’ Wilson, Ed Sanders, Carol Bergé, and ‘Crank’ Documented the Lower East Side’s Literary Avant-Garde,” American Comparative Literature Association annual conference; June 2022.

“Provisional New York Schools: Little Magazines & Generational Thinking,” Network for New York School Studies symposium, Paris, France; April 20, 2022.

“‘You are not great you are life’: 50 Years of Alice Notley’s Poetics of Care,” co-chaired roundtable at NeMLA, Baltimore, MD; March 3, 2022.

“Little Magazine Histories,” presentation for Dr. Caroline Crew’s course Editing a Literary Magazine, Warren Wilson College; Jan. 26, 2022.

“Such a Thing as New York School,” Interdisciplinary Modernism(s) Workshop hosted by Dr. Susan Rosenbaum and Dr. Nell Andrew at the University of Georgia, April 2021.

“Researching After the Last Avant-Garde,” inaugural NEH Fellow in Poetics Lecture at Stuart A. Rose Manuscripts, Archive, and Rare Book Library, Emory University; April 7, 2021.

“Living Library: How the Raymond Danowski Poetry Library Changes Literary History,” a five-part seminar hosted by the Fox Center for Humanistic Inquiry, Emory University; March 2021.

“We Love Our Lineage / Ourselves,” presentation on Ted Berrigan’s The Sonnets for Dr. Magdalena Zurawski’s Advanced Poetry Workshop, University of Georgia, Feb. 11, 2021.

“The New York School After the Last Avant-Garde,” presentation to Dr. Brian Glavey’s New York School seminar, University of South Carolina, October 23, 2020.

“‘Guided by Right Spirit’: The Radical Editorial Vision of Alice Notley and Douglas Oliver in Scarlet and Gare du Nord,” New Work on the New York School Symposium, Birmingham University, UK; July 6, 2018.

“‘Thinking of you’: The Sociality of Reading in Ted Berrigan’s Early Books,” Annual Conference, The 45th Annual Louisville Conference on Literature & Culture since 1900, University of Louisville, Louisville, KY; Feb. 24, 2017. Chair of panel.

“Poetry and the Living Archive,” Stokes Center Invited Faculty Lecture at the University of South Alabama, Mobile, AL; Feb. 7, 2017.

“The Archive is Alive at Emory,” with Katy Bohinc and Ali Power at the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archive, and Rare Book Library at Emory University, Atlanta, GA; Oct. 20, 2016.

“‘Many things are current’: Ted Berrigan’s Early and Ongoing Prose Works.” Annual Conference, American Literature Association, San Francisco, CA; May 28, 2016.

“Ted Berrigan, William Burroughs, and 1960s Mimeo Magazines.” Lecture in Dr. S.E. Gontarski’s course “Rethinking Textuality at the End of the Gutenberg Galaxy: Beckett, Burroughs, et al.” Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL; Sept. 29, 2015.

“Code Switching ‘the code of the west’: Clear the Range, Ted Berrigan’s Erasure Novel.” Annual Conference, Thinking Serially: Repetition, Continuation, and Adaptation Conference, The Graduate Center, CUNY. New York, NY; April 23, 2015.

“The Textual and Political Pleasures of Bernadette Mayer’s Utopia.” Annual Conference, MadLit 2015, “Dirty Talk: The Forms and Language of Pleasure.” University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI; Feb. 27, 2015.